Lucky in jewellery, unlucky in love: the women who bought fabulous jewels

Ganna Walska’ s life through jewellery

Visiting the Victoria and Albert Museum’s gigantic Cartier exhbition, I saw hundreds of fantastic pieces of jewellery and fabulous gemstones, but who were they made for? What parties did they go to or love affairs did they commemorate? Who were the women who bought these fabulous jewels? And why did they have quite so many husbands?

Touring the exhibition, I was curious about the women who bought from Cartier and the other major early twentieth century jewellery houses. Not only were they often fantastically rich, but their lives were as glittering and sometimes as strange as Cartier’s most extravagant creations. The women who bought these fabulous jewels were often lucky in jewellery, but unlucky in love, with a number of husbands far above the average (and who knows how many lovers?).

Ganna Walska: the Polish opera diva

If you were an opera goer or newspaper reader in the first half of the 20th century, you would certainly have heard of Ganna Walska (ca. 1887-1984). Although her talents as a singer were questioned by her contemporaries, she was an acknowledged beauty with quite the marital career. And, one with a taste for fine clothes and luxury objects. There’s an excellent round up of her matrimonial career here.

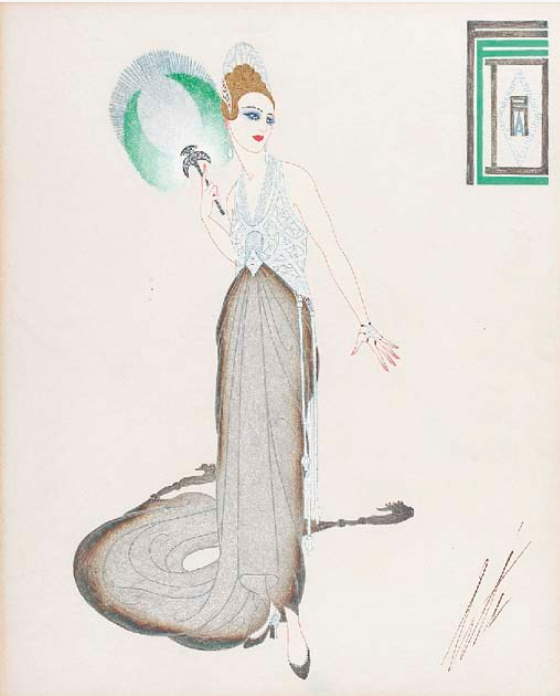

Walska’s career was largely shaped by her beauty and charm. Creating an unforgettable impression through dress and jewellery allowed her to shine both on the stage and in the salon.

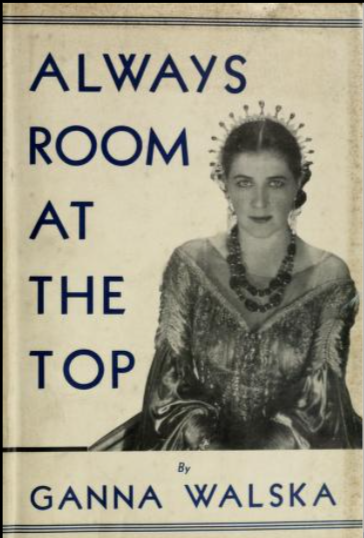

Her 1943 autobiography, ‘Always room at the top’ describes her jewellery in loving detail and she had plenty to enjoy. Fabulous jewellery was a personal pleasure, a way to make her way through the social scenery of Europe and America and part of her stage costuming.

While waiting to board a ship in Lisbon, she fretted over the fate of her ‘enormous jewel-case’, filled with emeralds, rubies, pearls and diamonds. She also enjoyed historic jewellery, such as oversized a la Russe diamond earrings and an impressive collection of original Indian jewellery. She prided herself on her individual taste, which caused her to reject small diamonds or tiny pearl necklaces as a matter of principle.

She didn’t have any reason to be embarrassed by her 96 carat yellow diamond briolette, (possibly bought from Cartier when her new husband Alexander Cochran gave her carte blanche to spend). It’s since been made into the pendant of a delightful bird of paradise brooch by Van Cleef and Arpels.

No tiny diamonds for Ganna

‘Liking jewels and fortunate enough to get them of any existing size and color, twenty years before the actual fashion for big gems, I designed for myself huge necklaces, bracelets and rings, and to make them, I got the biggest stones I could find on the market, the largest generous Nature created. Had I not had the means to get expensive big jewels, I would have preferred to wear large garnets, coral, aquamarines or other semi-precious and much less costly stones rather than small sapphires, emeralds or rubies. I never would have thought of wearing tiny diamonds or an almost invisible string of pearls that cuts the line of the neck unbecomingly and contributes nothing to the beauty of the face.’

Always room at the top, Ganna Walska

Luckily for Ganna, she didn’t have to suffer from the ignominy of miniature gemstones for too long. A series of marriages helped her to finance both her opera career and her jewellery habits.The first two husbands brought her into Europe and onto the opera stage but were soon jettisoned.

Husband number 3, Alexander Smith Cochran, was a carpet tycoon and, the then richest man in the world. According to Ganna, he was also the most miserable man she ever met. His jewellery gifts, though generous, she felt, lacked romance. After Ganna had been trying out the 1920s fashion for wearing multiple bracelets at once, he returned home to throw a parcel of gem-set bangles at her, according to Ganna’s account, wrapped in brown paper and rubber bands. Given that he had bought them from Cartier in his lunch hour, it seems doubtful that they would have sent him out without proper packaging. Nevertheless, Ganna was displeased. She was also disappointed by the gift for their first married Christmas – a beautiful heart-shaped diamond ring, again from Cartier, but given to her via her maid, rather than lovingly slipped onto her finger.

Ganna was a frequent and enthusiastic Cartier customer and they made some striking jewels for her. In 1929, she bought the first version of the ingenious rock crystal and diamond bracelet, with carved hemispheres of rock crystal arranged into a rounded bangle. Although it didn’t have a clasp, a clever coiled spring mechanism allows it to be put on and off.

Husband no. 4, Harold McCormick was more romantic. Recently divorced from Edith Rockefeller, the daughter of the richest man in America, he fell head over heels for Ganna, proposing multiple times before she was ready to accept him. McCormick himself was very wealthy through his ownership of the International Harvester Company and lavished money on Ganna’s operatic career. They met when she appealed for a chance to perform at the Chicago Grand Opera Company, and according to McCormick ‘I found her not only beautiful and talented, but possessed of spiritual qualities such as I never recognised before in any human being.’ (London Daily Chronicle, 17 October 1922).

Ganna’s stage costumes also called for fantastic jewellery, although she insisted that she only did so when the part called for it. The Second Empire gowns she wore on stage were so wide that she could only pass through the stage door sideways. She wrote that ‘each change of gown was accompanied by a change of jewels. With my enormous white satin gown I wore enormous diamonds; my brown costume blended harmoniously with rubies; the rich gold one with deep emeralds, black velvet with Oriental pearls and so forth.‘ (Always room at the top).

A taste for innovative jewels

Ganna didn’t just enjoy huge rocks – she also bought from some of the most interesting twentieth century designers. Suzanne Belperron, whose motto was ‘my style is my signature‘, supplied some exciting jewels. This eye shaped brooch, ca.1938, sets a mosaic of small gemstones around a large natural pearl. The dainty central panel is given importance by the smoky quartz frame.

A gold brooch, set with cabochon gems, looks like a curling costume moustache. Ganna wore this Belperron creation along with a pair of curving bangles, made of what the company called ‘virgin gold’.

The ‘unusual and exotic’

Ganna also loved ‘the unusual and the exotic’. She was awestruck by the jewels and turbans of the Maharajahs who attended the coronation of George VI in 1936, commissioning her own turbans to wear with her collection of Indian jewellery.

Walska describe the event as ‘the greatest spectacle of beauty, le plus beau theatre I saw in my life – and I have seen many. […] I was so impressed by its oriental touch that I had my Parisian modiste Suzy copy for me the turbans of all the Maharajas present at this magnificent event and with my collection of Hindu jewels I had exact replicas of something outstandingly beautifull’ (Always room at the top’)

She enjoyed original Indian pieces, like this bib necklace, one of the pieces sold in 1971, when she liquidated her astonishing jewellery collection to fund her garden at Lotusland near Santa Barbara.

Heiress and fellow jewellery enthusiast Doris Duke bought it for her own collection.

This diamond necklace was also part of the Parke Bernet auction in 1971.

Ganna Walska probably bought the original necklace from Cartier in the 1930s, set with flat Indian style diamonds on a foil backing. When Doris Duke acquired it from the 1971 sale, along with a pendant clip and earrings, she combined them all to make the current design.

Treasures from the Far East

Ganna also followed the fashion for Asian themed jewellery, promoted by Cartier, Lacloche and the other big jewellery houses. She owned a fantastical Cartier jade belt, made up of discs carved in the shape of Qing dynasty coins, a type of jewellery worn by Chinese officials.

Alongside her Asian jewellery, Ganna filled her house with luxurious objects. Cartier’s Asian inspired objects included a ‘mystery clock’ with a rock crystal disc with floating hands. The framework of the clock was inspired by the shape of a Japanese shinto gateway, though in a very Art Deco black and white colourway. The ‘billiken’ figure on the top was a good luck amulet.

‘Portico’ mystery clock, Cartier, ca. 1923.

Goodbye to all that

Ganna’s matrimonial career might seem a little like her prized Boucheron butterfly brooch – flitting from husband to husband, but eventually giving it up to focus on her true love, her garden at Lotusland.

Husband no. 5 was Harry Grindell Matthews, a Welsh inventor with a workshop on a mountain near Swansea, defended by 6ft high barbed wire fences. Grindell was a well known character, or perhaps charlatan, who had attemped to sell a ‘death -ray’ capable of stopping engines at a distance to the British government, but was unable to demonstrate under controlled conditions. His experiments in radio telephony took on a particular resonance in 1938 (though still failing to convince the government), when he married Ganna. Although his work kept him in Wales, he planned to fly over to Paris where Ganna owned the Champs Elysees theatre and a chateau for the weekends. His death due to a heart attack in 1941 ended one of Ganna’s most curious marriages.

Number six, the White Lama, fitted her interests in mysticism but alas, was otherwise unsatisfactory. Finally giving up on marriage, Ganna spent the remainder of her life creating wonderful gardens on her estate at Lotusland, perhaps finding more real happiness there than in any of her many marriages.

Further reading

Ganna Walska’s autobiography ‘Always room at the top’ is easily found second hand. Ganna’s niece Hania Tallmadge also published a book on her aunt titled ‘Portraits of an era’, 2019.

If you want more on society jewellery, try ‘A story of dukes, debts and pearl necklaces’.