Mesmerised! The Townshend gem collection at the V&A

Looking round a museum, It’s tempting to feel that the displays are natural and inevitable. However, every object in a collection came there through a particular route, some of which are more intriguing than others. The Townshend gem collection is one of those hidden stories.

When you go into the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) jewellery gallery, one of the first things you see is a spiral of sparkling gemstones set into rings. The gems are arranged according to the Mohs scale, with a central ring of coloured diamonds and radiates out towards the softest gems. Although the stones are set in rings, they were not all intended to be worn. Some of the stones, such as the two rings set with apophyllite and euclase, were much too fragile for practical use.

The display is interesting from a variety of points of view. First of all, it’s a spectacular introduction to the gem-set jewellery which creates such a dazzling display along the gallery. As the collection entered the museum in 1869, it’s a great resouce for gemmologists who want to study stones which are free of artificial enhancements such as radiation to improve colours.

Some of the stones are also notable for their prior owner, Henry Philip Hope, who died in 1839. Hope’s own fabulous collection of diamonds and coloured stones was split between his three nephews. The famous Hope blue diamond made its way to the Smithsonian Museum, while other gems were bought by collectors like Townshend.

Reverend Chauncey Hare Townshend and his gem collection

Chauncey Hare Townshend, the man who put together this wonderful collection, was born in 1798, at the very end of the eighteenth century. He was ordained as a vicar but took advantage of his large private income to lead a life devoted to poetry, music and collecting. According to his obituary in The Times, he was ‘a lover of art, and collector of rare judgement and exquisite taste.’ Alongside gemstones, he collected paintings, water-colours, cameos and coins. He was also an early photography enthusiast and collected works by the best English and French photographers of the 1850s and 60s.

Acquiring the Townshend gem collection was a major coup for the fledgling V&A, still then known as the South Kensington Museum. The museum’s curator, G.F. Duncombe, later described their encounter:

‘Some years ago, the Rev. Chauncy Hare Townshend…while walking with me through the Museum stopped to examine the jewels exhibited in the South Court, and to compare them with those in his own collection. Mr Townshend having no children, it occurred to me that it would be a noble thing for him to leave his collection by will to the South Kensington Museum, which at that time, had no precious stones except on loan. I made the suggestion to him and he seemed pleased with the idea, and subsequently often referred to it… I have since had the satisfaction of learning that about three years ago, Mr Townshend added a codicil to his will , by which he more than carried out the suggestion that I ventured originally to him.’

Mesmerism through gems

Townshend made friends with some of the key literary and cultural figures of his day. He hosted musical soirées at his London home which were attended by the poet Robert Southey and sensationalist novelist Wilkie Collins amongst others. He was a close friend of Charles Dickens who described him as a ‘poor dear fellow, good affectionate gentle creature’ and dedicated the first edition of Great Expectations to him.

Townshend’s will, proved in 1868, modestly described his collection as ‘rings set with gems intended to illustrate my geological collections’ but their appeal was not restricted to geology. He didn’t collect gemstones solely for their beauty and interest. He also used them in pursuit of one of his other passions, mesmerism.

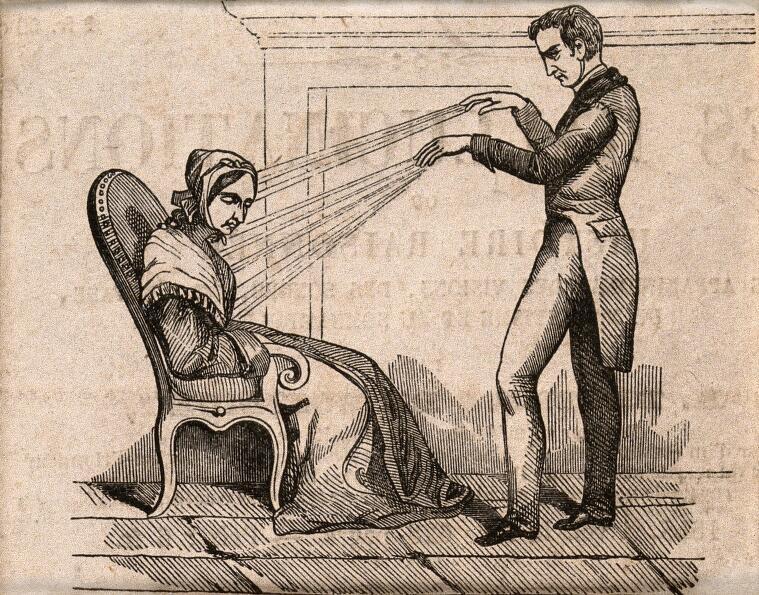

Mesmerism or ‘animal magnetism’ was popularised by Franz Anton Mesmer, a Vienna educated doctor who had taken Paris by storm in the late 1770s. Mesmerists believed that illness was caused by a blockage in one’s animal spirits and that the practitioner could make the patient better by remotely manipulating their spirits. Despite attempts to debunk it, including a commission headed up by Benjamin Franklin in 1784, it was still a very popular theory. Mesmerism became a cross between science and parlour entertainment, generally practised on unconscious women.

Agreeable feelings and soothing effects

Townshend and fellow mesmerists, including his friend Charles Dickens, thought that physical ailments could be cured through the manipulation of ‘animal spirits’ in the patient. Townshend believed that the natural properties of gemstones could affect the animal magnetism of his subjects.

The Townshend gem collection remains one of the highlights of the V&A jewellery gallery, but the story of its past use as a tool for mesmerism has largely been forgotten.

In his book ‘Facts in Mesmerism: With Reasons for a Dispassionate Inquiry Into it’ (1840), Townshend described his experiments using gemstones on sleepwalkers.

‘The diamond, when presented to the forehead of a sleepwalker, seemed inevitably to excite agreeable feelings; the opal had a soothing effect; the emerald gave a slightly unpleasing sensation; and the sapphire one that was positively painful. What is singular is that, if the last named stone was applied to Anna M–‘s forehead, she complained of its roughness, though it was perfectly smooth. While on the contrary, on contact with the diamond, which was cut into facets, she experienced a sensation of smoothness. One sleepwalker loved the diamond so much as to lean forward after it when I held it in my hand and to rub her forehead against it.

In general, however, I did not touch the patients with the gems, but held them concealed in my hand at a few inches’ distance from the forehead; and I changed their order sufficiently often to prove that the sleepwalker’s judgment of them was not accidental.’

This must have been quite a spectacle. Mesmerism had acquired a bad reputation and become associated with charlatans and cheats, although Townshend’s own belief appears to be sincere. As well as the experiments he conducted with gemstones (sourced from his impressive collection), he also visited various Victorian drawing rooms with a young German man named Alexis. According to the descriptions left by Fanny Kemble, Townshend blindfolded Alexis and placed him in a ‘mesmeric sleep. He then went on to read books aloud through his closed eyes, although Fanny Kemble was resolutely unimpressed. She greeted each demonstration with the words ‘Yes, I see it, but I don’t believe it.’

I wonder if Townshend was aware of the old medieval beliefs about the properties in gems, collected in dozens of lapidary books? His belief that gems had powers to affect mental and physical was one with deep historical roots.

The Townshend gem collection is in the Victoria and Albert Museum. For more ideas about great museums to see jewellery, click here.