Port and Starboard: the glamorous world of yachting jewellery

Yachts became the social must-have of the late 19th century, floating party palaces perfect for entertaining and offering a chance to show off nautical fashions and yachting jewellery. When The Tatler wrote about life in the English boating mecca of Cowes in 1909, they spoke evocatively of ‘sailing and racing, lunching and dining on land and sea, and showing off our smart frocks in the Squadron gardens.’

Yachting had the seal of royal approval, particularly from Albert Edward, Queen Victoria’s fun loving eldest son. It was also a popular pursuit for American millionaires and their pretty daughters. As well sailor suits, navy blue serge dresses, striped tops and peaked caps, jewellery for the yachting classes was a necessity. The Ladies’ Field in 1901 was still sceptical, claiming that ‘yachting jewellery is greatly advertised, but not I think often worn by the really best-dressed women. A few have the burgee of their husband’s or father’s yacht, in the form of a brooch, made of enamel and gold.’ Despite their opinion, the stage was set for yachting jewellery to flourish, both among the lucky yacht visitors and those who wanted some glamour by association.

Yachting itself was a hobby best restricted to the wealthy, as the London Daily Chronicle explained on 26 August, 1901: ‘Yacht racing is emphatically a pastime for millionaires, hardly possible for persons with moderate incomes, who desire to keep out of the Bankruptcy Court.’

Although yachting jewellery was worn by the aristocracy and millionaire yacht owners, made by firms like Cartier and Fabergé, cheaper options were available for those who wanted to share the fashion for the sea, despite their lack of a personal yacht.

Yachting jewellery styles

The 19th century saw a huge fashion for sporting jewellery, carrying over into the twentieth century. Yachting, as a popular sport, inspired the making of nauticallly themed jewels. Visitors to maritime towns, like Cowes in England or Newport in the USA, liked to buy souvenir jewellery from firms like Benzie of Cowes or Gieves. The Daily MIrror of August 1912 advised that ‘few people living on board a yacht go away without purchasing some piece of yachting jewellery. […] Bangles adorned with little jewels and enamelled port and starboard lamps are one of this year’s novelties, and jewelled burgees set in circles of diamonds are also to be seen. As ever, one of the most popular pieces of yachting jewellery is a bangle composed entirely of enamelled signal flags.’.

Jewellery inspiration came from all facets of yachting life. 1933 jewels for the seafaring woman included an ‘anchor brooch, a sailing yacht with diamond encrusted sails and yet a third brooch of crossed sculls in either gold or platinum.’

Yachting: a royal pastime

Like their English cousins, the Russian Imperial family were enthusiastic seafarers. Their yacht, Tsarevna, was used by Nicholas II and his son Emperor Alexander III and wife Maria Feodorovna (formerly the Danish princess Dagmar) along with their children. The Tsar was a member of the Royal British Yacht Squadron and sailed the Foros around the British isles.

Imperial jeweller Fabergé created several yacht jewels for the royal family, including an egg with a model of the Standart and jewelled brooches with the names of the Tsarevna and the Foros.

When Queen Alexandra visited Cowes in 1909, her high necked dress was decorated with a fashionable little flag shaped brooch. The King made his acknowledgment of naval life through a peaked sailor’s cap and naval uniform.

King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra at Cowes, Isle of Wight, 1909

Burgee brooches for yachting fans

The little triangular burgee flags flown on yachts or used by sailing clubs became a popular option for jewellery designers. Flag shaped pins and brooches set with gemstones or enamel simulated the colours of the ship or club or spelled out its name.

Each ship and sailing club had their own colours and devices, a fact known to any maritime fan. According to the Southern Echo of 1897, wearers weren’t always punctilious about their links to the boat or sailing club whose device they sported.

The Echo told its readers that:

‘For the last year or so “yachting jewellery” has appeared conspicuously in the shop windows, and the burgees of the best known clubs have been mounted either alone or in conjunction with a tiny enamelled life-belt as brooches, as pins, or upon gold wire for bangles. Yachtswomen, of course, understand the significance of such things and would not dream of fastening a tie with a device they were not entitled to use, but their less instructed cousins, who merely regard them as quaint and fanciful “latest novelties”, as numbers have done, especially on their seaside holidays, may be astonished to find that with such colours they may have been sailing very closely to the wind in the use of armorial bearings.’

Southern Echo, 22 September 1897

Burgee flags found their way into tie-pins, brooches, bracelet charms and even pencil-holders and vanity cases.

Alongside the more affordable enamel pins, jewellery houses like Cartier, Van Cleef and Arpels and Marcus and Co. offered burgee pins set with precious gems, like this undated sapphire and diamond Royal Yacht Club, London pin (Christies). The framework of the brooch has been cleverly shaped to suggest a flag blowing in the wind.

In the early 1930s, Cartier made a pair of cufflinks, set with of domes of crystal reverse painted with the pennant of the New York Yacht Club and an image of USS Vamarie. The Vamarie was commissioned by Vadim Makarov, a former Russian naval officer and later caviar importer, in 1933 as an ocean racing yacht. He donated it to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1936 and it was used in Naval races before seeing service in World War II.

Makarov married the American heiress Josephine Hartford in 1931 and it’s tempting to think that the cufflinks were a gift from her.

Signalling your intentions

Club flags weren’t the only naval flags to be made into jewellery. Messages at sea could be passed through a dictionary of flags, each one signifying a letter or a common phrase. Combining these flags in jewellery allowed messages of affection, friendship and good wishes to be be communicated. Using naval flags in jewellery came into fashion in the 1890s and continued in use throughout the twentieth century.

In 1931, The Tatler showcased ‘Jewellery for the Yachting Enthusiast’ by Gieves of Old Bond Street, London. Alongside the well known burgee flags, they included ‘International Code’ jewellery, like a bracelet set with a series of flags and a silver pencil holder enamelled with a series of flags.

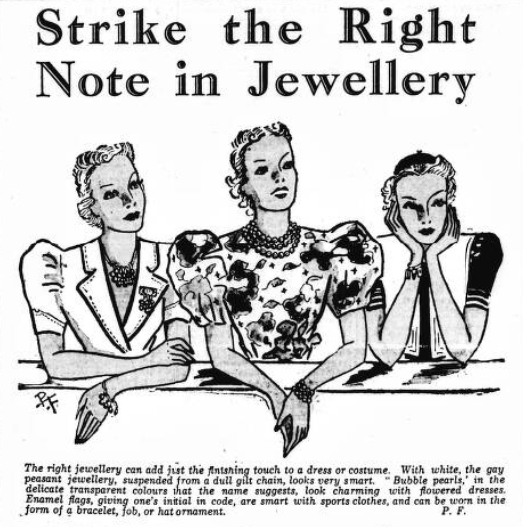

According to The Evening News, August 1937, ‘Enamel flags, giving one’s name in code, are smart with sports clothes, and can be worn in the form of a bracelet, fob or hat ornament.’ Over in America, Raymond C. Yard’s catalogue of 1939 offered bracelets with flags spelling out ‘I love you’ or ‘Sweetheart’, appealing objects for the eve of war.

A piece of jewellery spelling out a message in naval flags, or even the whole naval alphabet, was a fun addition to a yachting themed outfit.

Port and starboard earrings

The naval convention of showing a red light for the port or left side of a vessel and green for the starboard or right, was a useful way to determine the direction of travel. It was also a fun detail to bring into jewellery and accessories.

In 1912, the Gold and Silversmiths’ Company offered a masthead light charm in either port or starboard, to hang on a bracelet or watch chain. By 1931, the Illustrated Sport and Dramatic News was touting a table cigarette case shaped like a ship’s lantern, with red and green lights.

1950s jewellers developed red and green port and starboard earrings. The Daily Mirror, January 1957, described it as ‘a new fashion for women who are keen on sailing’.

Port and starboard earrings were part of a fashion display at the National Boat show at Olympia in 1957 and 1958, the Mirror claiming that seven out of ten new members of yacht clubs were women. The ‘fashion afloat’ corner offered ‘play-suits patterned with nautical phrases, brooches hand-painted with the colours of a yacht club’s burgee – and “port and starboard” earrings.’

The fashion spread fast – in 1960, when socialite Lady Kitty Crane sailed off for a three month holiday to South Africa, she wore a gold brooch shaped like a ship’s wheel and miniature port and starboard earrings. Lady Kitty wasn’t the only fan – in October 1970, the Daily Express reported that tattoed trawlerman Wallace Deans was banned from every English pub for fighting and drunkenness. He was easily recognisable by his red and green port and starboard earrings as well as the birds tattooed on his cheeks.

Sporting and yachting jewellery remains a fun way to commemorate your hobby, match your sporting wardrobe and turn details of boats and naval life into jewelled accessories.

For more on sporting jewellery, try this post on tennis.