Edmund Waterton’s ring collection at the V&A: pride, eccentricity and bankruptcy

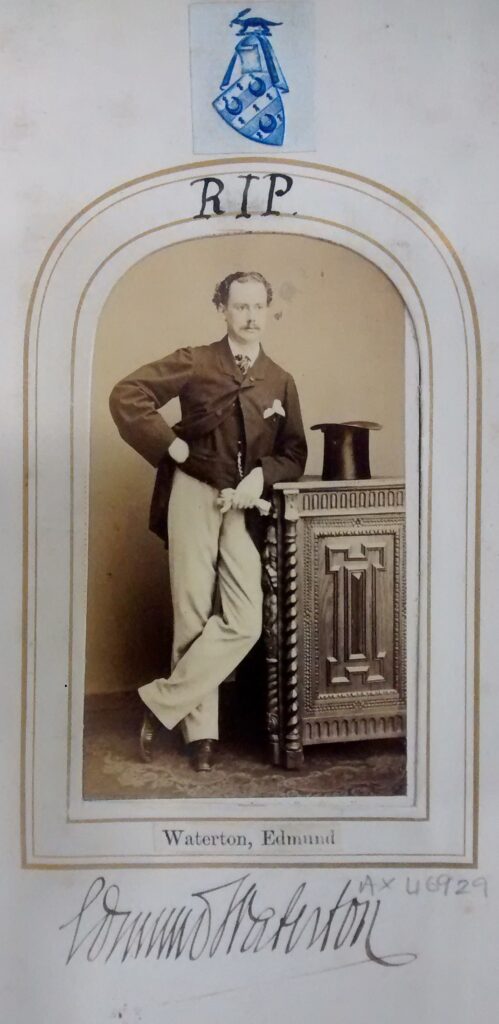

Edmund Waterton (1830-1887) is the collector you’ve probably never heard of. However, his fabulous collection of historic rings now fills the cases of the Victoria and Albert Museum Jewellery Gallery. Edmund’s life of eccentricity, extravangance and collecting led him to bankruptcy. But, the happy result of it was that Edmund Waterton’s ring collection, through being put in pawn, was kept together and sold to the V&A.

Edmund began with many advantages but ended his life having lost almost everything he’d accumulated. So what went wrong? Many of the odder aspects of Edmund’s life can probably be put down to his upbringing.

Early life

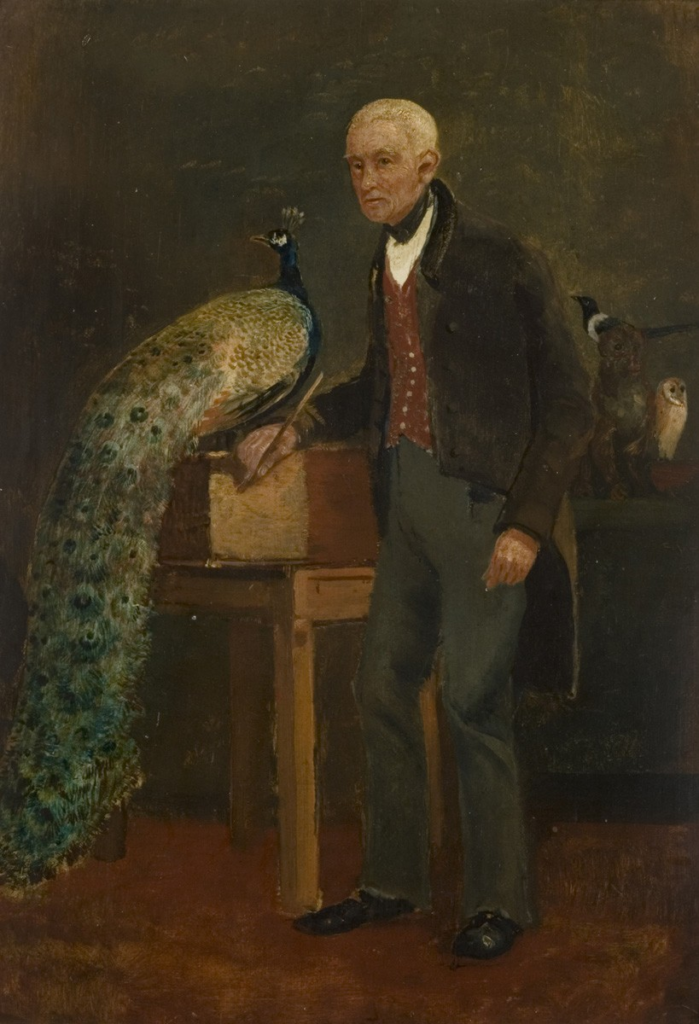

Edmund’s father Charles was a fascinating character, one of the nineteenth century’s great eccentrics. He was passionatetely fond of nature, becoming a pioneering conservationist. As a young man, he travelled to Demerara, part of the colony of British Guiana to work as a manager on the Waterton family’s sugar plantations. He was responsible for supervising the enslaved people forced to work on them. Charles was far more interested in nature than commerce and he soon slipped away to travel into the interior of the country and discover its wildlife.

Charles’s love of nature led him to collect and preserve specimens of birds and animals. He was proud of developing his own methods of taxidermy – by hollowing out his specimens and preserving them through the use of chemicals.

He also prided himself on his taxidermic creations and jokes, using them to criticize aspects of modern life he disliked, such as Britain’s heavy public debt. These very strange creations were left to his school, Stonyhurst College.

‘A constant though silent mourner’

When Charles was 47, he married Anne Edmonstone, the daughter of Charles Edmonstone, his old friend from Demerara. She was only 17 at the time.

Charles was struck with grief after the death of his young wife. He took refuge in his strong Catholic faith but also developed unusual and ascetic habits. He prided himself on being able to stand on his head, lead a life of monastic simplicity, slept in a room without any glass in the windows and dressed shabbily. Edmund was brought up by his aunts Eliza and Helen, who had followed their sister Anne when she married Charles. The Edmonstone sisters were descended from a plantation wood merchant and grand-daughters of ‘Princess Minda’, the daughter of an Arawak chieftain.

So, Edmund was brought up in a very unusual household. The poor health of his aunts and his father’s religious preoccupations led the family to travel across Europe to find a more suitable climate for the sisters and to visit religious shrines.

Eliza was responsible for the household and Charles clearly placed a great deal of trust in her. When he died, his will left the family estate of Walton Hall to Eliza and Helen rather than to Edmund, already in debt.

When Edmund went away to Stonyhurst College (England’s first Catholic boarding school), he must have breathed a sigh of relief. He had left the strange household of his grieving father and two maiden aunts and moved into a world of people his own age. He also took his first steps into collecting with relics and small precious objects.

The collector

Collecting was clearly a family interest, but while Charles focused on natural history, Edmund’s interests lay in the decorative arts. Even at school he filled his room with religious relics, prayer books and decorative objects.

Edmund was a passionately devout Catholic. He put together what is still the largest collection of the medieval devotional text, the Imitatio Christi by Thomas A Kempis. We can get a good insight into his attitude as a collector from the words of one of his book dealers:

‘One of the pleasures of his life was to see the foreign packets come by post. He kept an oblong volume like a washing book, with all the editions that he knew of , some thousands in all and his chief delight was ticking one more off the lengthy desiderata like a schoolboy marking off the days of the holidays’.

ROBERTS, ‘A book hunter in London’, quoted in HOLBROOK, Jackson. The anatomy of bibliomania, originally New York, 1950, reprinted Chicago, 2001

Apart from the Imitatio Christi, his main focus was on rings. Collecting rings was a very popular 19th century pursuit. They were available in reasonably large quantities, certainly compared to other kinds of historic jewellery. They were also fairly affordable, small and easy to store. In addition, rings could be used to demonstrate the development of style in jewellery. They were also links to famous historic figures or a way to show changes in social practices like marriage.

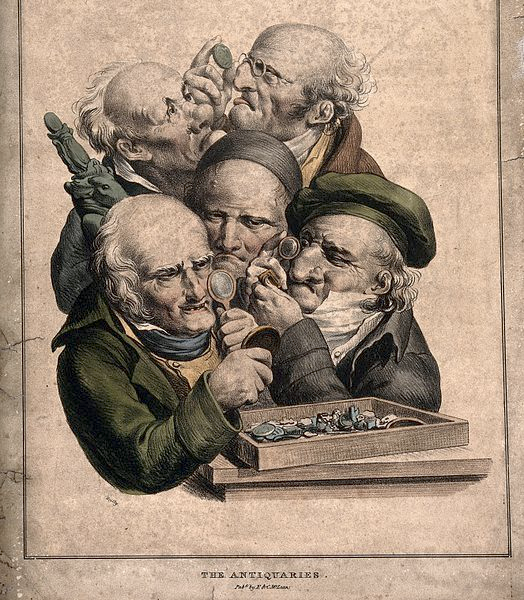

Collectors often organised themselves into scholarly societies. This access to people with complimentary interests was one of the appeals of collecting. Edmund’s ring collection gave him entry to the Society of Antiquaries, the Archaelogical Society and put him on friendly terms with other collectors like Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, whose collection is now at the British Museum, Charles Drury Fortnum who left his collection to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and Michelangelo Caetani, the Duke of Sermoneta, in Rome.

Other collectors like Ernest Guilhou and Louis Fould in France and the Koch family in Germany (whose collection has recently gone on display in the National Museum in Zurich) established ring collecting as a serious academic pursuit.

Edmund’s ring collection

Waterton’s intention for his collection was to present a chronology of ring design. The earliest rings are from Pharaonic Egypt, the latest from the early nineteenth century and the collection includes many fine Roman, medieval and Renaissance rings.

This beautiful medieval sapphire ring was given to Waterton by the traveller and fellow book collector Sir Robert Curzon. According to Waterton’s records, it was taken from the tomb of a bishop in France. Bishops often wore sapphire rings as the blue of the sapphire was thought to be close to the blue of heaven. Although Edmund probably bought most of his rings from dealers, he generally recorded any personal gifts or impressive provenance.

The collection also reflects some of Edmund’s principal interests. His religious sensibilities are mirrored in some of the very beautiful medieval religious rings he collected, along with a small group of early Christian rings. His Catholicism and connection with the Papal court is evident in a series of 13 extremely large base metal rings, set with glass or rock crystal and decorated with the arms of various Popes or Cardinals. Although their purpose is still unclear, they might have been used a safe conduct for papal messengers. Or perhaps they were made as impressive objects for the avid 19th century collector?

Edmund, like his fellow collectors, particularly liked rings which he believed to be associated with famous historical figures. The ‘Darnley ring’ was one of his prized items. It was long thought to be the betrothal ring of the romantic and doomed Mary Queen of Scots and her second husband, Henry Darnley. The front of the bezel is engraved with the initials M and H with a lover’s knot whilst a rather crude inscription on the back reads ‘Henri L. Darnley 1565’. Later scholars have suggested that this inscription may be a later addition but it is certain that Waterton firmly believed it to be original.

The Dactyliotheca Watertoniana

Waterton approached his collection in a very serious way. One of his unfinished tasks was putting together a full catalogue of his rings, the rather grandiosely named Dactyliotheca Watertoniana. His introduction lays out his ambitions and also suggests that if the Dactyliotheca had ever made it into print, it would have been quite a slog to read.

“Of all the ornaments with which mankind has ever delighted to adorn itself, there was none more favourite nor more universally adopted than the Finger Ring. As a signet, in its primitive form, it was of the greatest importance, and of the regal rings it might literally be said that in their hands the Rings held the fates of many men, for, in ages gone by, the impression of their ring was equivalent to the sign manual of our days. As an ornament, it afforded the opportunity of lavish expenditure, and incredible sums were spent on rings and gems. […]

This collection has been formed for the object of illustrating the history of finger rings in chronological order from the earliest times down to the eighteenth century… Many collections exist, but none of them have been formed on the principle I laid down for my guidance. I bought the first ring in 1853, and the collection has been steadily increasing ever since. It has now become well known, and the many complimentary notices of it which have appeared in the magazines and other publications, lead me to believe that an illustrated catalogue will not be unacceptable to archaeologists, and to the public at large.

Now, although Pliny says that ‘it is, indeed no easy task to give novelty to what is old, and authority to what is new; brightness to what is become tarnished, and light to what is obscure’, still Seneca justly observes that ‘ Si omnia a veteribus inventa sunt, hoc semper novus erit usus et inventorum at aliis scientia et dispositio. [But even if the old masters have discovered everything, one thing will be always new,—the application and the scientific study and classification of the discoveries made by others.] This is my justification for what appears in the following pages and for any shortcomings, I address to my readers these lines of Ovid:

‘Da veniam scriptis, quorum non gloria nobis causa, sed utilitas, officium que fuit ‘ [Be kind to my writings whose purpose was not my glory , but their usefulness and the duty they performed]”

The great unravelling

Edmund’s life was described by a Yorkshire neighbour as ‘a brief career of pride, folly and extravagance’. His love of fine living and his expensive collecting caused money to run through his fingers. Charles had clearly become worried about the fate of his estate and the nature reserve in Edmund’s hands and decided to leave everything to Eliza and Helen, the sisters in law he had spent his life with. Perhaps the most shocking moment in Edmund’s life came after his father’s death. He took his two aunts to court to have the will overturned, threw out his father’s papers and opened up the nature reserve for hunting and fishing. If it wasn’t for Eliza and Helen’s efforts, none of Charles’ research, letters or taxidermy would have survived.

Despite this, Edmund’s debts continued to mount. Eventually, his prized rings were the only thing left to pawn. He handed them over to the London jeweller Robert Phillips against a loan of £1000 to be repaid in 1870. By 1869, Phillips approached the new South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) to offer the whole collection. The museum’s board and curators were quite familiar with the collection as it had been on display in the 1862 Special Loans Exhibition. They accepted the offer enthusiastically, along with the unpublished manuscript of the Dactyliotheca.

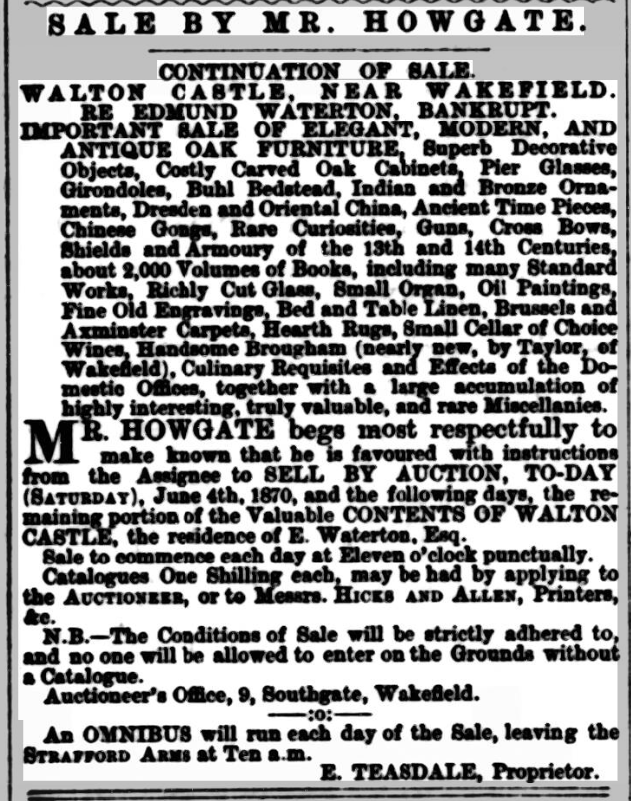

Edmund’s troubles continued. He was forced to sell Walton Hall and even his furniture was put up for auction. A notice in the Wakefield Express, 4 June 1870, offered the contents of Walton Hall (renamed as Walton Castle by Edmund). Edmund’s antique oak furniture, Dresden and Oriental china, ancient time pieces, Chinese gongs, rare curiosities and about 2000 books were all up for sale.

Interested bidders had only to buy a catalogue for a shilling and take the omnibus which had been laid on to participate.

At the end

Although losing his collection must have been a hard blow for Edmund, it did allow it to be kept together. While most of the ring collections of the 19th century were dispersed, Edmund’s survives in its original form. His identity as a collector and scholar was maintained despite his extravagance leading to catastrophe.

Another V&A ring collector: Rev. Chauncy Hare Townshend.

Dear Madame Dear Sir, I am an archaeologist specialised in ancient gems and working scientifically. For a contribution strictley academic I am looking for a Roman gold ring with a cameo with inscriptions which is published by C.C. Oman, Victoria and Albert Museum Dept. of metalwork: Catalogue of Rings (1930) p. 56 Nr. 140 (Waterton Colln.) Can you help me with that? Carina Weiss

There should be a list of museum inventory numbers at the back of the catalogue. You can use these to find it on the museum database here https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections?type=featured or you can search under object type, materials or date.