Loss and love in the first World War

In 1912, Arthur Morley Jones, a young bank clerk, commissioned the artist Reginald Oswald Pearson to make a set of jewellery as a engagement gift for his fiancee Mary Houseman. Three years later, the first World War had swept them into dramatically different directions, leaving the jewellery as a souvenir of loss, love, friendship and the way in which war turned the lives of these two young men upside down.

An engagement gift

Jewellery made the perfect engagement gift. When Arthur Morley Jones became engaged to fellow clerk Mary Houseman, he commissioned several jewels for her. Rather than heading to a high street jewellery shop, he turned to his brother Sydney Langford Jones’ friend from the Royal College of Art. Reginald Pearson’s interest in medieval art led to a group of beautiful Arts and Crafts style jewels. They were kept in the Pearson family until they were donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1995.

Gold, sapphire and moonstone brooch and ring by Reginald Pearson, 1912. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Alongside the necklace, Pearson made a brooch, decorated with a pattern of vine leaves and grapes, and hung with a large luminous moonstone. The accompanying ring, also decorated with a scrolling leaf pattern and set with cabochon sapphires, was engraved with Mary’s initials and the date of the engagement, 5 September 1912.

Reginald Oswald Pearson: the jeweller

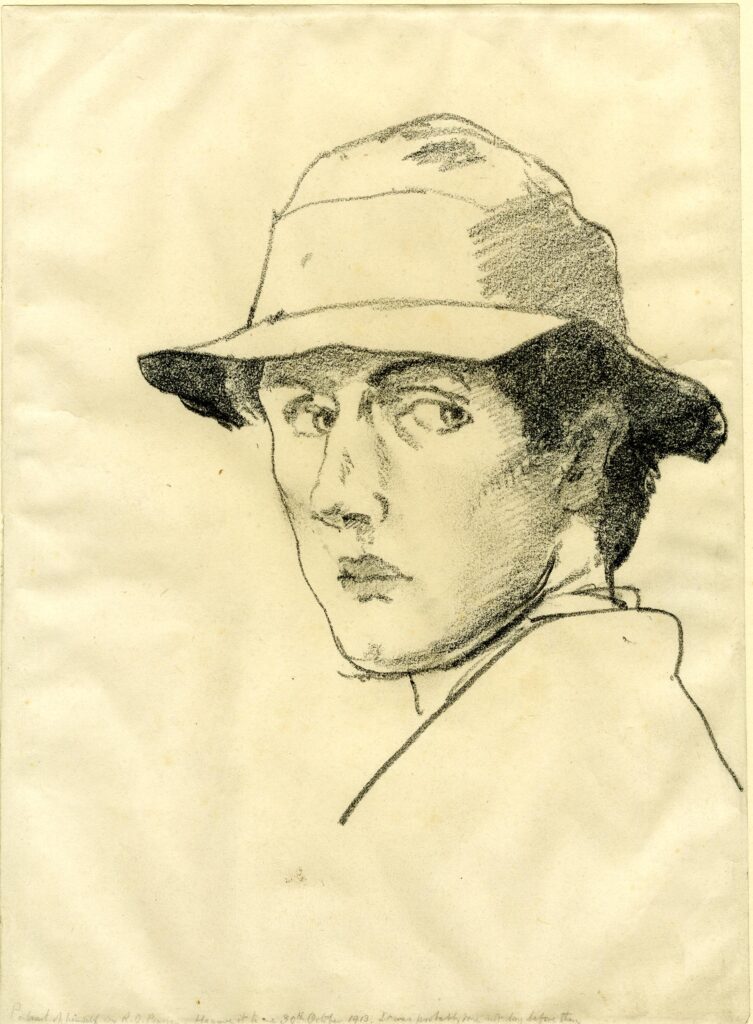

By the time Arthur and Mary married on 27 April 1915, the First World War was into its second year. Reginald Pearson (1887-1915) had signed up at the start of the war in August 1914, as a member of the Artists’ Rifles, a volunteer battalion which had been set up in 1859 and which attracted painters, musicians, actors and architects.

Pearson was a member of the Regular Battalion in the Lincolshire Regiment, listed in the Regimental Roll of Honour of the Artists’ Rifles. Like many regiments, the death toll was appalling. 2003 members of the Artists’ Rifles died in the 1914-18 war, including Pearson. The regiment’s Roll of Honour recorded, with typical jingoism, that ‘this moment, without frivolity, […] these boys, all of them, looked death straight in the face, laughing and smiling, and that the Artists earned at that time the sobriquet of ‘The Suicide Club’.’

On the 16 June 1915, Pearson was reported missing near Hooge, Belgium. Hooge was part of the Ypres Salient, an intensely fought over area which saw enormous casualties on both sides. Like many soldiers, his body was lost in the mud of the battlefield.

His name is recorded on the Menin Gate memorial at Ypres and on the memorial in South Walsham, his Norfolk village.

Pearson’s experience of war is brought vividly to life in a letter he sent to his friend Sydney Langord Jones (Jonah), Arthur Morley Jones’ brother. Poignantly, it’s postmarked 15 June 1915, a day before his death.

B Company 1st Bat. Lincolnshire Regiment

British Exp. Force

My dear friend Jonah

How I wish I could have seen more of you and I even wanted to turn back that Saturday night and catch you up to say goodbye again.

Since then I have really seen the horrors of war such as I never dreamed possible, marching at midnight with a lovely moon through the famous old town you have heard so much of, flaming all over the place and not a single house untouched. Stones, bricks, paving stones in what was once the roads, putrid bodies under the heaps of broken bricks once houses, and furniture blown out of the windows.

The old Cathedral and Hall as big as the Doges’ Palace and once very fine I should think now but a skeleton of ragged bones rapidly growing less and less, and the cemetery, no longer sacred, is blown to atoms with holes in it 40 yards round without the slightest exaggeration, for I measured one, and hemispherical shape, and the whole town a collection of foul vapours, still being shelled, shelled, shelled.

From there we were marched to a wood full of dugouts where we remained all next day being shelled, losing many men.

About 4 o’clock the whole lot fixed bayonets and travelled through the wood arriving at a communication trench by dark, full of mud up to the men’s thighs, hundreds of shots fired over it to catch as many as possible who happened to get out.

Along this [wading?] trench about 6’ deep and so narrow the men struggled passing those who were coming out, and eventually I found myself in the most extraordinary position ever created, but which I must not mention though I could draw you a perfect map from memory.

Trenches scarcely 3’ deep, parapets and bullet proof, strobing over dead men, bullets, bullets everywhere and the next 3 days cannot be spoken of. Trenches blown in beyond all recognition, and the first thing I saw when down broke was a dragoon with a little cat on his lap, which he had been stroking, lying both dead right across the trench, horrible, horrible, horrible.

I lost 18 wounded, 3 killed and 1 officer seriously wounded and here was I for the 1st time in charge of nearly a Company in the worst position ever held. Strategically bad, too few men, and for every German shell which came intermittently, every 20 I ought to say, we acquired a little pill in return.

9 miles march 3 days – the trenches 9 miles out with no sleep, little food and small shot, would offend the nostrils of death himself, leave men a bit fatigued, and so my first experience of war is passed and as a matter of fact I did well.

So much for my troubles for at present I sit in an orchard where we are bivouacked, resting.

The God of all the men we love is with me, I know, and this wonderful help and guidance are seared on my brain.

I am too tired to write much and so I must say goodbye.

God bless you always

Your dear friend

RO

Letter from Reginald Oswald Pearson to Sydney Langford Jones Berkshire Archives (D/EX1795/1/5/2)

Remembering Reginald Pearson

It would be too sad to remember Pearson only by his death, rather than the art he dedicated himself to.

His obituary, printed in the Arts and Crafts journal The Apple in 1920 describes his love of craftsmanship and tradition, describing him as:

‘an independent mind, determined to take nothing on trust and above all to avoid all “modern” theoretical experimentalism’.

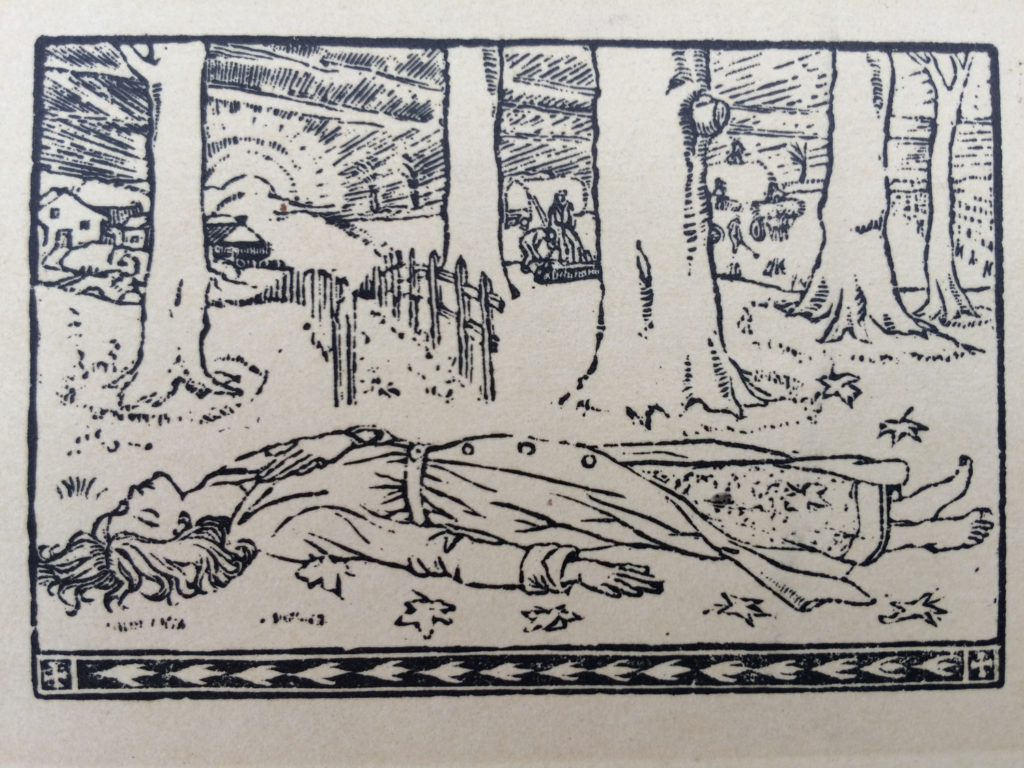

This appreciation for artistic tradition can be seen in the jewellery he made for Arthur Jones, the engraved design and cabochon gemstones directly inspired by medieval art. It’s also apparent in his prints and engravings, now at the William Morris Gallery, London. He worked in stained glass, print making, poetry and jewellery with the same sensitive eye. Where might his art have gone had he survived the war?

Arthur Morley Jones: the client

We don’t know whether Arthur Morley Jones and Reginald Pearson were personal friends but the request to make the jewellery must surely have come through Arthur’s brother, Sydney. Sydney and Reginald were both students at the Royal College of Art, while Arthur had started work at the London County and Westminster Bank when he left school in 1904. Nevertheless, he must have appreciated finely crafted jewellery to choose such an extensive commission for his engagement to Mary.

While Reginald enlisted as soon as the war began, Sydney and Arthur made a different choice. Both were committed Baptists and refused to participate in the war in any form. While the first years of the war attracted huge numbers of volunteers, sometimes whole streets or factories would join up in ‘Pals Battalions’, by March 1916 so many soldiers had died that mass recruitment was necessary. Herbert Asquith’s government introduced conscription, originally for single men between 18 and 41, later extended to married men like Arthur.

Any eligible man who refused to serve would be arrested if he did not claim an exemption. Men with a sincere religious objection could put their case forward to a tribunal and if successful, would be registered as conscientious objectors.

Both Arthur and Sydney applied for a total exemption, not just from serving as a soldier but from support for the war in any form, whether through work on a farm, as a stretcher bearer or ambulance driver. In the records of their tribunal they both stated that:

I believe that all military work, & all work that facilitates or promotes military work is contrary to the teaching of Jesus Christ.

Central Military Service Tribunal and Middlesex Appeal Tribunal: Minutes and Papers, Case Number: M623 [and M118} http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/.

Objecting to serving in a ‘non-combatant corps, Sydney explained that:

My “objection covers any form of military service, combatant or non- combatant, & also any form of civil alternative, under a scheme whereby the government seeks to facilitate national organisation for the prosecution of war.”.

Central Military Service Tribunal and Middlesex Appeal Tribunal: Minutes and Papers, Case Number: M623 [and M118} http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/.

Although they were excused from active service, their application for total exemption was refused, with painful consequences. There was intense social pressure to support the war – able bodied men might be mocked in the street and handed white feathers by judgmental women. There must also have been a feeling of guilt, seeing friends join up and die, leaving bereft families.

There were more consequential results than social shaming. When Arthur appealed for a total exemption in July 1916, he was working such long hours at the bank that he could not attend his own hearing. By the time his tribunal was recorded in The Middlesex Chronicle, 2 September 1916, he is listed as ‘no occupation’. Had the bank dismissed him as a result of his decision to become a conscientious objector?

Explaning why he would not serve as a member of a ‘non combatant’ unit, he placed his choice as ‘a charge of abscence from an Army to which he did not belong’ versus ‘the charge of desertion from Jesus Christ, to Whom he did belong’.

Military authorities had little sympathy for conscientious objectors. The needs of the front, especially after the huge losses on the Somme, required a constant replenishment of soldiers. Allowing men to escape conscription posed a risk of contagion which the authorities were unwilling to risk. A handwritten note on Arthur’s tribunal papers makes this attitude clear:

I do not recommend leave [to appeal]. If any force is to be given to our direction that there must be Sacrifice of some Kind – then this man has really no appeal whatever. Should be required to serve in the Non-Comb. Corps. [Signed] H.Nield, 24 vii 1916.

Arthur was fined 40s and handed over to the military, although eventually discharged as unfit to serve.

His brother Sydney made the same choice but met an even harsher fate. Many conscientious objectors, including Sydney, were sentenced to prison, often under very difficult conditions. Sydney’s statement that he would not take any part in the war as ‘I cannot do what I sincerely believe to be wrong. I cannot sin against my conscience‘ inevitably led to imprisonment. Sydney’s records show him committed to prison at Wormwood Scrubs for two year of hard labour (commuted to 112 days), followed by a period in Pentonville prison. Conditions, as women suffragettes had previously discovered, were deliberately hard, with poor food, cruel treatment and hard physical labour. Many conscientious objectors were permanently harmed or killed under this regime.

Although conditions in prisons could not be compared to the horrors of front line service, soldiers at least had the approval of society and could feel they brought honour to themselves and their families.

Even if society disapproved of conscientious objectors, Reginald Pearson may not have done. His last letter to Sydney Langford Jones is a very fond one, even though Sydney had already refused to serve by then. Perhaps Reginald was happy that his friend was comparatively safe from the war?

After the war

The jeweller and artist Reginald Pearson disappeared in June 1916. Tragically, as his body was never recovered, his mother hoped that he had been taken prisoner rather than killed, until her own death in 1918. Both Arthur and Sydney Jones survived the war. Arthur and Mary had two children, Katherine and Robert. Mary’s jewellery passed to Katherine, who donated it to the Victoria and Albert Museum, along with the family memory that its maker had been lost, presumed killed, in the first World War.

This pretty set of jewellery, made on the eve of the First World War, became not just a treasured family heirloom but the lasting souvenir of a talented young artist and his friendship with two young London men. Though Reginald Pearson’s war was very different to that of Arthur and Sydney Jones, each of them followed their conscience with great courage.

Further reading

There is an excellent account of Sydney and Arthur Jones’ experiences as conscientious objectors here http://smothpubs.blogspot.com/2014/11/ealings-conscientious-objectors-case.html

For more on wartime jewellery, I’ve written about some of the odder wartime materials here: