S is for Snake: understanding symbolism in jewellery

S is for Snake

In the jewellery alphabet, S may be for Skull but it could also stand for Snake. Snakes are not the most obviously romantic or decorative motifs, but they slithered into jewellery in antiquity and have never really left. S is for Snake – understanding symbolism in snake jewellery leads us to jewels of romance, grief, eternity and beauty.

The snake is a powerful and ambiguous symbol. It was associated with healing deities – Isis in Pharaonic Egypt or the Greek god of medicine, Asclepius. In the form of the royal cobra, snakes adorned the crowns of Egyptian pharaohs.

Snakes symbolised regeneration, healing and rebirth and became a symbol of eternity, particularly in the form of a snake biting its own tail to form a perfect, endless circle. This association with regeneration and eternity led to their use on both love and mourning jewellery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

But, snakes in literature and art can also be negative forces, associated with evil and the underworld. The snake in the garden of Eden is a symbol of temptation and human weakness. The snake in the grass or in the bosom symbolise treachery – an interesting disconnect with romantic snake brooches and pins.

The jewelled snake in antiquity

Perhaps the general form of the snake suggested itself to jewellers? The long body of the snake, coiled around the finger or arm, naturally shaped itself into a ring or bangle. Snakes could also be entangled in decorative and puzzling loops on brooches and buckles. Snakes wrapped themselves into jewels, in single or multiple loops, with engraved decoration to represent their scales. Sometimes they featured bright little jewelled eyes.

A golden bracelet from Roman Egypt uses the imagery of the snake to fantastic effect. The snakes are linked with different deities and convey a message of luck, love and eternity. It’s a fabulously intricate object with layers of imagery.

Snakes and goddeses combine to make a beautifully sculptural and rich object.

Egypt (Roman period), 1st century BCE to 1st century CE. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Two densely patterned snakes form a Herakles knot in the centerpiece. The snake on the left represents Agathodaimon, and the cobra on the right Thermouthis, deities associated with Serapis and Isis, respectively. The two goddesses in the centre are Isis-Fortuna, the personification of Alexandria and Aphrodite, the goddess of love.

This bracelet uses imagery from the legend of the great Greek hero Herakles. As the infant son of Zeus and the human queen Alcmene, he became the target of Zeus’s wife Hera’s jealousy. She sent two snakes to attack him in his cradle, which, due to his supernatural strength, he killed with his bare hands. The Herakles knot, set with a garnet, in the centre of the bracelet shows his victory over the serpents.

Hellenistic snake bracelet, 3rd century BCE – 2nd century BCE. Schmuckmuseum, Pforzheim.

Snakes almost caused the death of baby Herakles but for other babies, they may have been a protective amulet. In Euripides’ play Ion, Creusa places golden snakes with the baby she is about to abandon, perhaps in the form of a snake bracelet or clasp.

Two snakes carved in gold. The goddess Athene

insists that all new-born babies are given them.

Yours were copied from your grandfather’s.

Two gold snake bracelets ornamented the body of a young Romano-British girl who was buried at Southfleet in Kent in the 3rd century CE. Perhaps these were jewels she had worn in life, buried with her to protect her in her journey through the afterlife?

Roman jewellers followed the example of earlier Greek artists and created many lovely gold snake jewels, full of life and naturalism, twisting the snake’s body into loops and circles.

Snake bracelets, like most bracelets, were often worn in pairs. The golden mummy mask of twenty year old Aphrodite shows her dressed for her journey to the afterlife. She wears a pair of large two-headed serpent bangles which stretch over most of her lower arms.

Snakes were associated with the goddess Artemis and a large number have been excavated from her sanctuary at Olympia, offered as donations to the goddess and to call for her favour.

Mummy cartonnage, 50-70 CE, Egypt (Roman period). British Museum.

The fashion for pairs of serpentine bracelets was a long -lasting one.

Snake bracelets decorate the arms of an extraordinary nut-cracker from Roman Taranto. The hands are hinged so that the palms can press together and crack open a nut. Each bracelet is carefully modelled in gilt bronze, showing an open-jawed snake head at the top and bottom of the bracelet.

Taranto, Contrada Rondinella, tomb IV | Late 4th – early 3rd century B.C. National Archaeological Museum, Taranto, Italy.

The eternal snake of love and death

Snakes appeared to regenerate themselves by shedding their skin but they were also linked to eternity through the motif of the ouroboros or ‘tail-devourer’. Often represented as a snake or dragon biting its own tail to form a circle, it symbolised the cyclical nature of time.

When the ouroboros appears in jewellery, it is a symbol of eternity. It is found in both love and mourning jewellery. From the seventeenth century, mourners often wore jewellery with the name and life dates of their lost friend or relative. Testators frequently left money and instructions in their wills for mourning jewellery.

A ring made to commemorate Captain Newman Newman, who died shipwrecked in Jutland in 1811, is formed of a gold and black enamel snake which curls around a bezel enamelled with a Union Jack flag. The snake is a symbol of mourning and hopeful resurrection while the flag is a reminder of his earthly career.

Memorial ring for Captain Newman Newman, 1811. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Snakes and turquoise combined in a mid nineteenth century necklace. The turquoise symbolised love and friendship. It was thought to protect the wearer from danger but also to change colour if the donor or wearer’s affections changed. The bright blue also echoed the colour of the forget-me-not, a symbol of love in the language of flowers popular in the nineteenth century.

Hearts combine with a looping snake to send a message of love in a jewel given to Victoria by her mother the Duchess of Kent in 1832. The little hearts are engraved with the initials of the two eldest children of Princess Feodora Hohenlohe-Langenburg, Victoria’s half sister.

Image: Royal Collections Trust

Snake jewellery was enormously popular in the Victorian court in romantic and mourning jewellery. In 1839, Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria a snake shaped engagement ring which he had designed himself. It was set with emeralds for the eyes and was a romantic promise of everlasting love.

After Princess Victoria, Duchess of Kent (Queen Victoria’s mother) died in March 1861, Prince Albert designed a brooch set with the Duchess’s portrait and encircled by a pearl serpent as a gift for Victoria. The pearls symbolised purity and the snake eternity.

Sadly Albert died before the bracelet was finished and it became a posthumous present. Victoria had the back engraved ‘Last gift / from my / beloved & adored Albert / ordered by him / for Xmas 1861 / Given me by Alice / Jan. 1st. 1862’. It was one of the objects which was placed in the ‘Albert Room’ with her most prized sentimental jewels when she died.

Bracelet clasp with portrait of Victoria, Duchess of Kent. Royal Collections Trust.

The fashionable snake

Perhaps because of their association with love, death and eternity, snakes were hugely popular in nineteenth century jewellery. The fashion may also have been encouraged by the passion for archaeologically inspired jewellery prompted by excavations of the ancient world and the rediscovery of the lost city of Troy by Heinrich Schliemann in 1873.

Snakes appeared in rings, bracelets or wrapped around the neck as a collar or necklace. In Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, 1862, the deceptive Lady Audley was shown

‘…holding out her little fingers, all glittering and twinkling with the diamonds she wore upon them. He looked at her pretty fingers one by one; this one glittering with a ruby heart; that one encircled by an emerald serpent, and about them all a stary glitter of diamonds.’

Lucy Audley has the trappings of worldly success and love – expensive diamonds given by her husband, a ruby heart as a sign of passionate love and the serpent ring of eternity. But all is not as it seems and perhaps the emerald snake is a suggestion of her true identity as a bigamist and murderer.

Both men and women wore snake jewellery. In the 1822 short story Mr P’s Visit to London, the eponymous Mr P. met his rich London cousin and remarked that ‘I instantly perceived that there was a serpent in his bosom, which he wore as a brooch’.

Snake jewellery was fashionable at the highest levels of society. For men, it generally found its way into rings, tie pins or brooches or perhaps mourning jewels.

George IV wore a snake ring on his little finger when he was painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1822. The ring itself is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

George IV, Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1822. Wallace Collection.

The young Duchess of Manchester was painted by Elish Lamont in 1852 with her baby daughter. She wears a large gold snake bracelet on her wrist and a wedding ring.

Image: National Portrait Gallery, London

The wealthy American socialite, Mrs William Astor had a fabulous snake ring according to the newspapers from February 1894. The ring’s clever construction allowed it to writhe around her finger in an eye-catching way.

Snake rings appeared in literature as well as in life. In an 1879 story entitled Dr Olibrius’ Snake Ring, the hero was given the ring by the titular doctor. According to the dying doctor, it had the power to fascinate women.

‘It was a trinket of three coils, made of priceless rubies, and having diamond eyes. So wondrous was its glitter – so brilliantly did every stone flash out, although there were no sunbeams to reflect that the Baron could not take his eyes off it. He twirled it round his finger, rubbed it on his sleeve, and turned it every possible angle towards the light.’

The Graphic, 28 June 1879

The Baron finds that the ring is so firmly fixed to his finger that he is completely unable to remove it, until he is safely married and his bride pulls it off. His snake ring was both a love token and a slightly sinister jewel with magical qualities, nullified only by lawful true love.

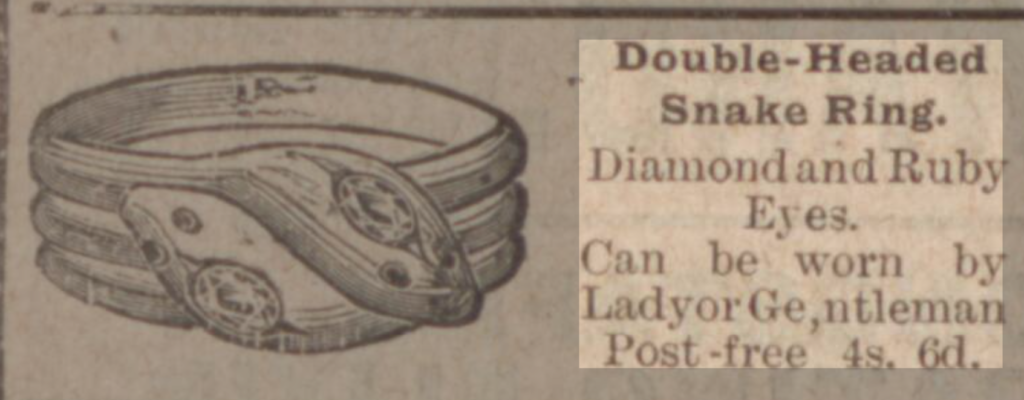

The Baron’s snake ring was a gorgeous and expensive object, set with rubies and diamonds. Slightly cheaper examples can be found in newspaper adverts and catalogues.

This advert from The Million, 29 June 1895 illustrates a double-headed snake ring made of imitation gold and stones, suitable for either a male or female customer.

Ancient Greek or Roman snake rings might also be an option. Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen collected a museum’s worth of classical gems, jewels, pottery and sculpture to inspire his neo-classical sculptures.

Thorvaldsen wore a gold Roman snake ring for over twenty years, probably presented to him by Queen Caroline of the Two Sicilies. The ring functioned as a fashionable piece of male jewellery but also reinforced his engagement with classical art and his self-presentation as an artist.

Image: Thorvaldesens Museum, Copenhagen

Snake rings were still fashionable in 1905, listed in the account of a ‘Smart wedding at Haslingden’. Alice Tomlinson, daughter of a cotton manufacturer, married Joseph Parker, the son of another cotton magnate. She gave him a diamond snake ring and a set of silver brushes, suggesting that an early twentieth century middle class man could wear a diamond set snake ring with perfect propriety.

They were still so popular in 1915 that a Birmingham jewellery firm advertised for youths and boys to learn how to make signet and snake rings.

The modern snake jewel

Ideas about snake jewellery have changed since the nineteenth century and it has lost some of its romantic associations but it remains a popular design. Vogue editor Diana Vreeland certainly felt so when she wrote her 1968 memo on jewellery fashions.

“Don’t forget the serpent… it should be on every finger and all wrists… the serpent is the motif of the hour in jewellery… we cannot see enough of them”

Diana Vreeland, 1968

Bulgari’s Serpenti line and Boucheron’s Serpent Boheme testify that the serpentine remains a potent force in fashion.

In the contemporary jewellery world, Clio Saskia’s tiny, life size jewellery sculptures embrace the quirkiness and charm of the natural world. Her gold and Australian sapphire Knuckleduster Ring stretches across the hand, twisting its head to look back at the wearer. It’s modelled on a tree-dwelling green cat snake and adds a touch of edgy glamour to any hand.

More on jewellery symbolism

For more on jewellery symbolism, try A is for Anchor, B is for Butterfly, M is for Moon and S is for Skull.