The Art of Movement- Van Cleef and Arpels

Should jewellery ever be a static art? Jewellery is made to be worn, to move with the body or clothing. One of the elements we miss when looking at jewellery in a museum or gallery, is movement. The new exhibition by Van Cleef and Arpels, The Art of Movement, seeks to address that problem. It’s the first dedicated exhibition the house has shown in London but hopefully not the last.

The Paris based Maison of Van Cleef and Arpels was founded in 1906 with a focus on fine jewellery made to the highest technical standards. A display of 98 jewels, supported by archive drawings, brings the history of the house to life.

Looking at jewels through the lens of movement brings natural objects such as flowers and feathers, movement through dance, the relationship of jewellery to dress and fashion and movement viewed through art.

The exhibition

The exhibition at London’s Design Museum (23 September to 20 October, 2022) begins with a large anamorphic sculpture, inspired by the 1937 Silhouette clip. It’s a tangle of wooden ribbon which flows through the gallery spaces, guiding the visitor through four distinct zones.

Nature Alive

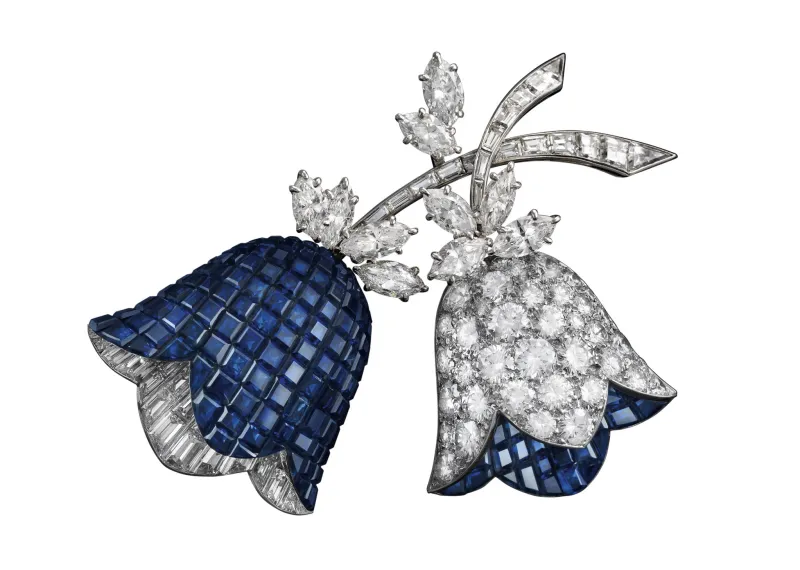

The exhibition guides the visitor through the use of different coloured pleated silk backgrounds. Nature Alive, the first section, uses a pale blue colour which tones with the floral jewels on show.

The first section features jewels inspired by nature – flowers and feathers created from gorgeously coloured gemstones. The trademark mystery setting brings the petals of flowers, like the bright blue bellflower clip from 1969, to sparkling life.

Displaying original designs alongside the jewels is a nice touch. Customers chose their jewels based on the designs drawn up by jewellers. It’s interesting to see how closely many of the designs match surviving jewels.

Pretty little flower clips, shaped like buttercups and daisies, sit alongside roses carved out of pink tourmalines. Many of the clips date from the late 1930s and 40s, despite the exigencies of the Second World War. Although the jewellery trade in Europe was very restricted, Van Cleef and Arpels set up an operation in America to sell their jewels to their USA patrons.

Dance

Dance is an art form inseparable from movement. Louis Arpels’s love of dance, to which he introduced his nephew Claude, inspired a whole range of jewels.

Tiny ballerinas made from diamonds, rubies, turquoise and coloured gold pirouette in the display cases. In fact, one display uses motorised wires to move the ballerina clips up and down and allows them to twirl. Although the dancers faces are made of a single rose diamond, the figures are full of movement and detail. As well as classical ballet, designers took inspiration from other forms of dance, like the tiny Balinese dancer clip.

In 1967 Claude Arpels inspired the choreographer George Balanchine to create the Jewels ballet. Balanchine took inspiration from diamonds, emeralds and rubies to create an innovative ballet. Van Cleef and Arpels continue to support dance by commissioning contemporary dance choreography.

Dancers also appear in the Princess necklace – a golden circle formed by the whirling skirts of ballerinas, seen from above.

As well as contemporary dancers, the 1730 painting by Nicolas Lancret also inspired a brooch. Mlle de Camorgo caused a scandal by shortening her ballet dress to show her legs and feet. Her rounded skirt with its scalloped edge can be recognised in several brooches.

So far, all the dancer jewels are based on female artists. Is it time for a male dancer to join the troop?

Elegance

Jewellery and dress have always gone hand-in-hand. In 1925, Vogue magazine complained that ‘the dresses are so plain that they need to be set off by even more than mere beauty – and what can one add but jewels?’

The section of the exhibition which focuses on fashion is displayed against soft pink pleated silk. It’s a riot of dress clips, brooches and necklaces.

Clip brooches, often made to split into two separate brooches, are a particular feature of the mid-twentieth century. They clip to the neckline or shoulders of dresses and attach to bags or even hats. The exhibition shows a lovely ribbon double-clip from 1938 made of platinum and diamonds. It has a wonderful three dimensional quality due to the mixed cuts of the diamonds. Round and brilliant-cuts on the front of the ribbon contrast with baguette cuts on the back.

Smartly dressed women also needed little bags and minaudieres or vanity cases to carry their lipsticks, cigarettes and other small items. The exhibition includes a lovely example with a surface on which stylised flowers stretch out like peacock feathers.

The Zip necklace

The Zip necklace is one of Van Cleef and Arpels’ most iconic jewels. It’s truly a technical tour de force. Designers first used zippers in clothing in the 1920s, first for uniforms and aviator outfits. Men’s trouser flies and children’s clothing followed. High fashion soon adopted the zip – it was modern, daring (what goes up can also come down) and allowed a slim silhouette. Couturier Charles James used it in his 1932 ‘Taxi’ black satin cocktail dress, in which a zip wrapped around the body. Following his example, Elsa Schiaparelli shocked reporters with her use of contrasting zip colours in her 1935 -6 collection.

It’s not surprising that Renée Puissant, Van Cleef and Arpels artistic director, dreamed of bringing the zip into jewellery. She was perhaps inspired by Wallis Simpson, one of the most stylish women of the twentieth century. However, creating a moveable, working zip from solid metal was a challenge. Designers finally achieved it in 1950, after twelve years of development.

The exhibition shows both a necklace and a bracelet. The wearer zips up the necklace by moving the fastener up the teeth inside the loop. Once you get to the top, removing a small section of metal straightens the curve to form it into a bracelet. Most of the pieces made for clients are unique, but in this case, the customer requested an identical second piece so that she could wear both necklace and bracelet together.

Abstract movements

The final section looks at how art movements are reflected in the house’s jewellery. Modernism, Op Art and wooden, rounded jewels made in the 1970s show the influence of wider art movements on jewellery

It’s been a great year for jewellery in London. For my review of the Platinum Jubilee exhibition at Buckingham Palace, Tiffany’s show stopping exhibition and the Tiaras show at Sothebys, click here.