Gladstone’s axe: how to brand a politician through jewellery

Modern politicians spend millions on personal image making and branding, but this is far from a new invention. Nineteenth century politicians also wanted to create a strong personal image and commission souvenirs which could be worn by their followers to attract support and intimidate opponents. A wood axe became a surprising way to brand the British politician William Gladstone through jewellery.

William Gladstone: the Grand Old Man

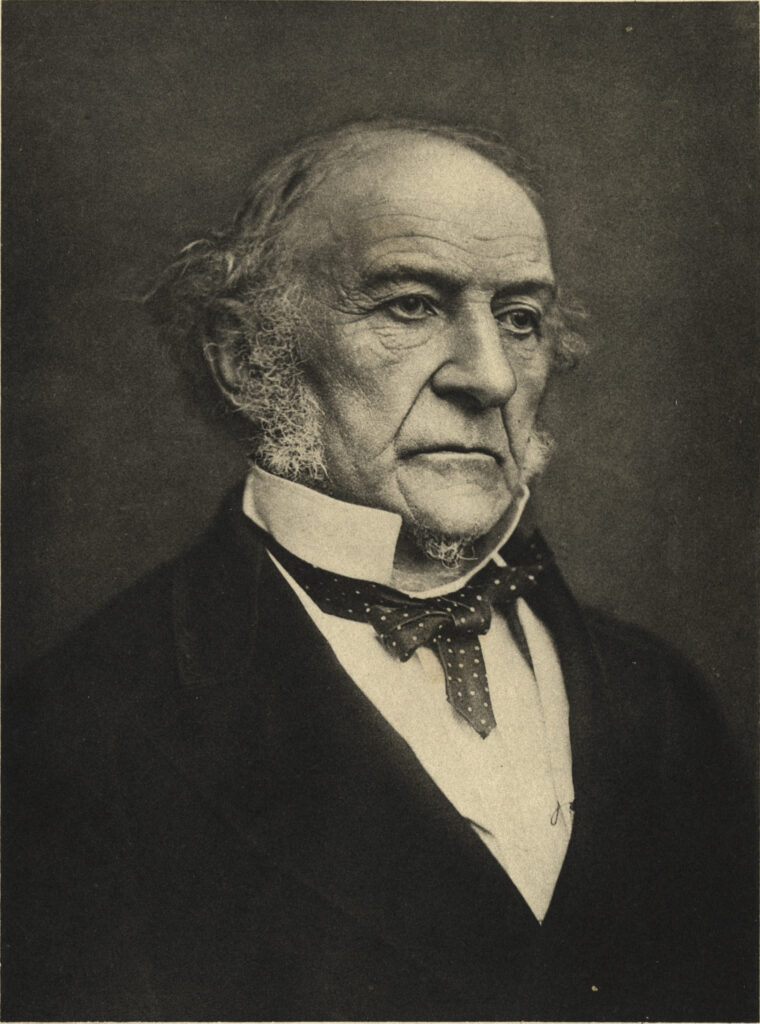

Liberal politician William E. Gladstone (1809-98) was described by Queen Victoria as a ‘half-mad firebrand’ but to the wider British public, he was a supporter of democracy and the widening of the franchise (though not yet for women). He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer and, had four stints as Prime Minister, a record yet to be beaten.

Gladstone associated himself with major causes such as the promotion of Home Rule for Ireland, the widening of the electoral franchise to include men who owned or rented property worth more than £10 per year and was a strong supporter of free trade.

Gladstone was painted, photographed and appears in hundreds of cartoons and prints, but one of the most intriguing ways he was presented was through souvenir jewellery.

‘Tried, Trusted, True’ – Gladstone election jewellery

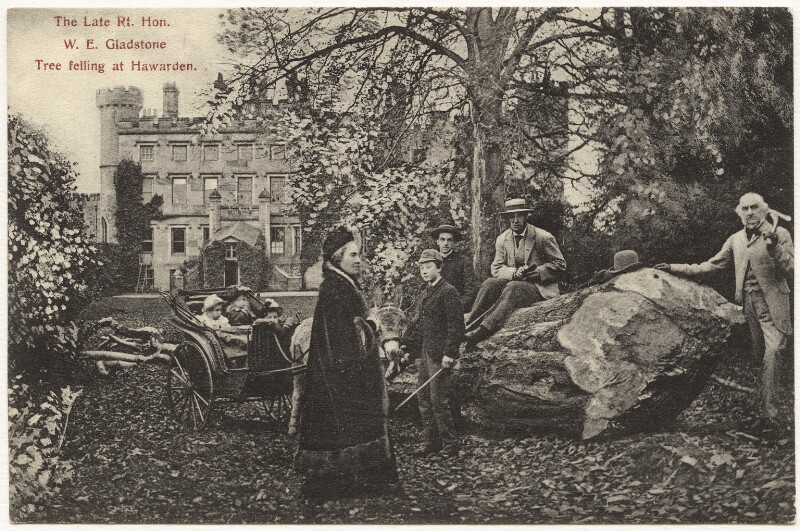

Gladstone took up tree felling as a hobby in 1858, as a way to work off excess energy. Watching Gladstone cut down trees in his estate at Hawarden became a well known public pastime. Gladstone used tree cutting as a metaphor for improving the health of the British state. He made an explicit link between cutting out the rot in trees and removing corruption from public affairs.

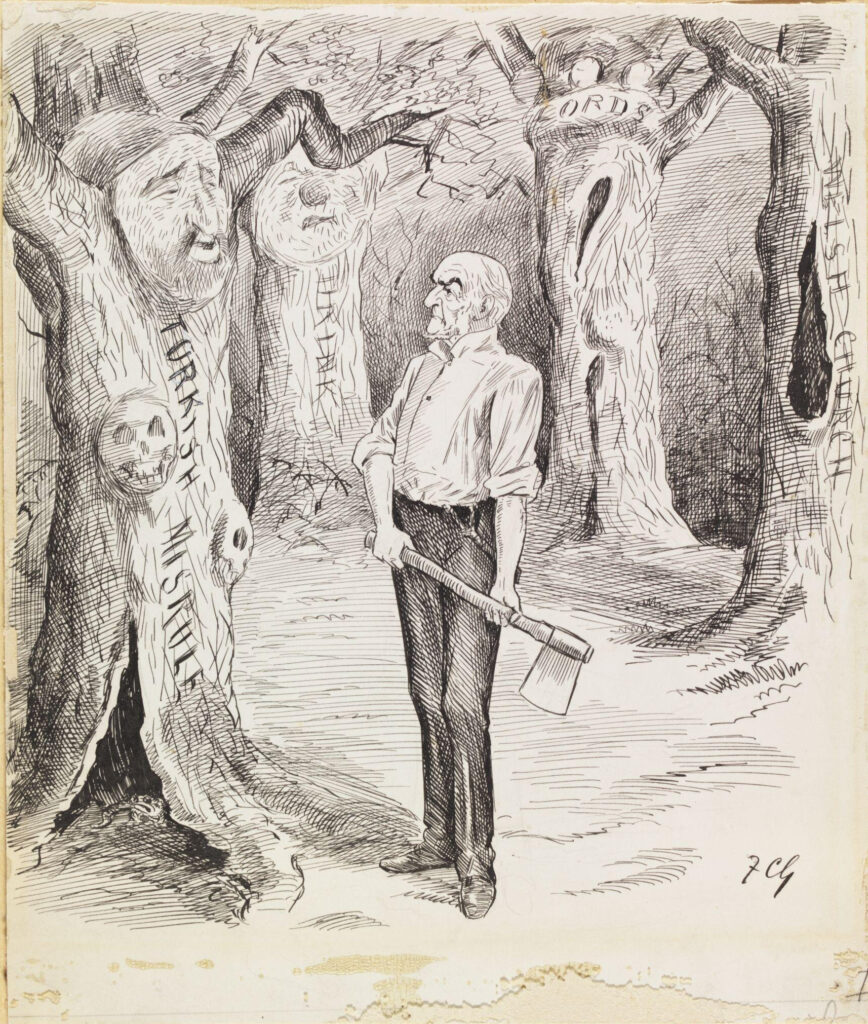

This 1867 caricature by Sir Francis Carruthers Gould shows Gladstone, axe in hand, tackling problems such as ‘Turkish Misrule’ and the Irish Church.

His political enemies also used his tree-cutting hobby as a means of attacking his policies. According to Lord Randolph Churchill:

‘For the purposes of recreation he has selected the felling of trees; and we may usefully remark that his amusements, like his politics, are essentially destructive. Every afternoon the whole world is invited to assist at the crashing fall of some beech or elm or oak. The forest laments in order that Mr Gladstone may perspire.’

after Samuel E. Poulton

postcard print, (circa 1888). National Portrait Gallery, London

Gladstone was so closely associated with axes that he received them as gifts, notably a silver axe for his 69th birthday in 1878. He was also invited to cut down or trim trees when visiting friends and family or even on political campaigns. In fact, any one who invited Gladstone was well advised to have a sacrificial tree in mind, in order to satisfy his need for exercise. In 1874, a Liverpool newspaper described him as he ‘walked home with his axe slung over his shoulder… looking not tired or weary but refreshed’ just before a political meeting at Hawarden.

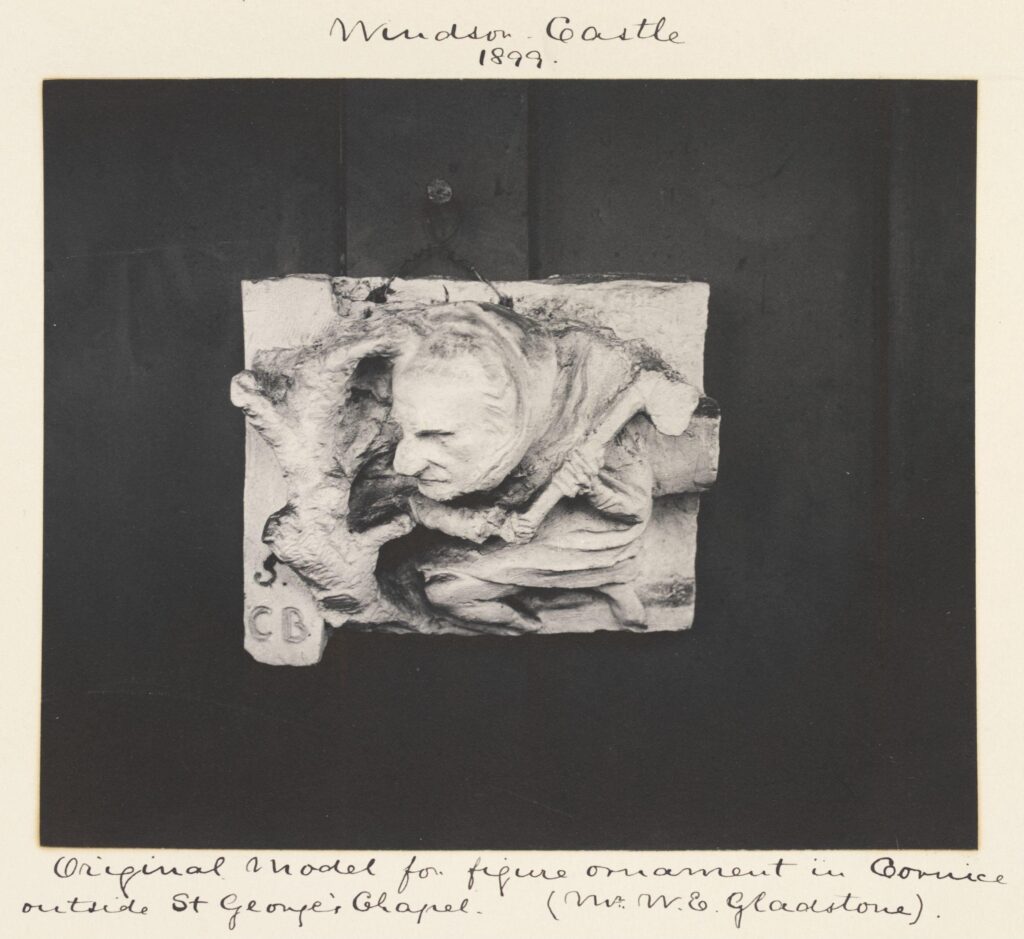

The Birmigham electroformed brooch above was designed in 1883 according to the design registration but not made until 1898-9, demand perhaps increased because of Gladstone’s recent death. This jewel included a portrait of Gladstone, alongside his trademark axe and felled tree.

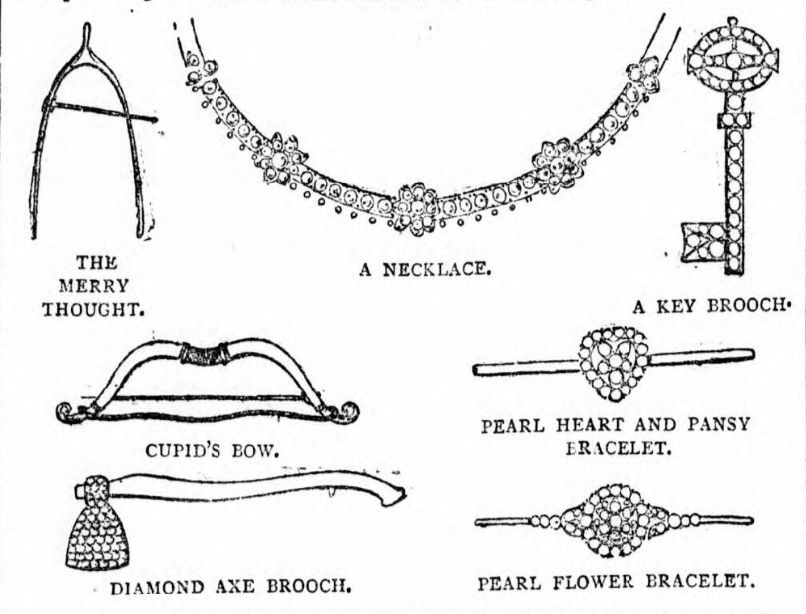

A diamond and oak jewel shaped like an axe, sold by Hunt and Roskell of London, allowed the axe to stand in for the statesman. Described as ‘the axe of the Grand Old Man in oak and diamonds’, it was apparently not as much of a success as the primrose badge linked to Gladstone’s great rival, Benjamin Disraeli.

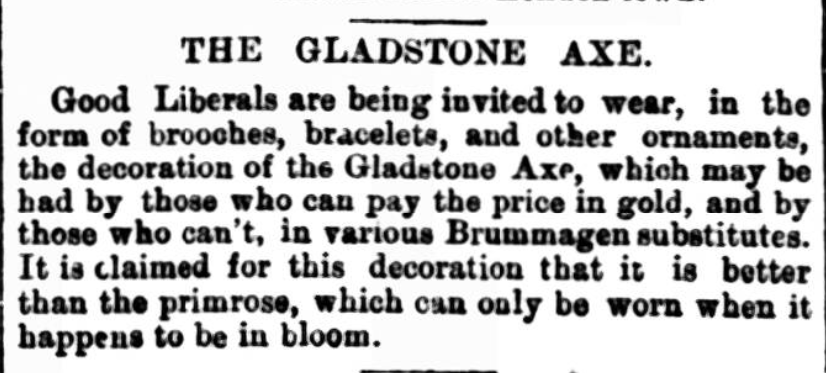

According to the Buckingham Express, Saturday 21 November 1885, the Gladstone Axe jewel had become an official campaign ornament, with good Liberals being invited to wear axe themed brooches, bracelets and other ornaments. These were available in gold for the well off, and for poorer supporters, what were rather rudely described as ‘Brummagen substitutes’, the frequent description of Birmingham factory made goods.

As a demonstration of how to brand a politician through jewellery, Gladstone’s tree cutting hobby was extremely successful. Considering the length of Gladstone’s career and the adoption of the axe as an official campaign jewel, it’s surprising that so few of them seem to survive. The British Museum has a gold cravat pin in the shape of a log split by an axe, dating from 1879, which is very likely to be a Gladstone campaign jewel, instantly recognisable to contemporary observers. Although very few jewels are currently linked to Gladstone’s campaigns, it’s likely that many late nineteenth century British axe shaped jewels were in fact pieces of Liberal political merchandising.

For more on nineteenth century men and jewellery, here is the account of explorer Henry Morton Stanley‘s ring and the sad death of the French Prince Imperial.

Text copyright Rachel Church.

What is the value of this badge?

I have one with the axe head in gold.

Hi, they don’t seem to come up for sale too often, but there is one listed on Worthpoint which you could check.