Henry Morton Stanley’s ring, I presume?

What would you take if you were setting off to explore central Africa? A nice pith helmet? A machete to hack through the vegetation? A pistol? One of the items the controversial explorer Henry Morton Stanley particularly valued was a silver ring, presented to him before he set off on the Anglo-American Expedition in 1874. Looking at Henry Morton Stanley’s ring opens up a story of male jewellery, presentation rings and a very star-studded wedding.

Mr Stanley’s missing ring

We know about the ring because of a newspaper article from 1890. It is titled ‘Mr Stanley’s Missing Ring’ and reports that, before setting off on the Anglo-American Trans Africa Expedition, Stanley was presented with a ring engraved with his name, that of the expedition and the date. He wore this throughout his travels around Zimbabwe and central Africa in search of the headwaters of the great Nile river.

Perhaps inevitably, considering the ardours of the journey, he lost it. According to the article, in an unlikely twist of fate, it resurfaced eight years later. Aided no doubt by the commemorative inscription and Stanley’s fame, a Welsh missionary bought it and returned it to him as a present for his forthcoming wedding.

In 2002, the auctioneers Christie’s held a substantial sale of objects relating to Stanley. Among the photographs, maps and memorabilia was a silver ring. It’s quite a humble object- a wide band set with a shield shaped bezel on which is engraved the explorer’s name, the expedition and its dates but it’s tantalisingly close to the description in the article (if we accept that the expedition end date was added subsequently).

Stanley the explorer

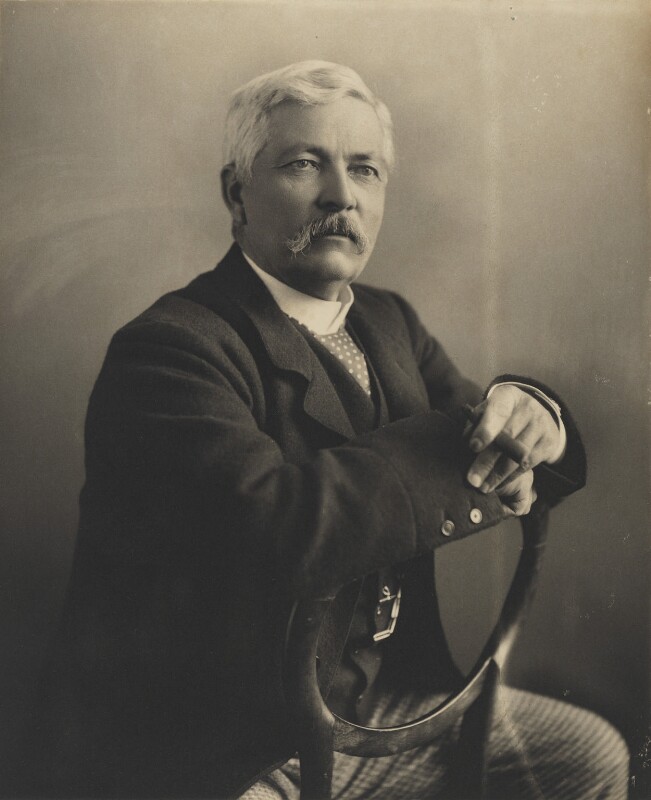

Henry Stanley was a famous figure in the 19th century, both as a journalist and an explorer. His voyage to find lost fellow explorer David Livingstone was immortalised by his fabled (and probably fabulous) greeting ‘Dr Livingstone, I presume?’. In 1874, he was commissioned by the Daily Telegraph and the New York Herald to map out the rivers and lakes of central Africa.

His story was the ultimate rags-to-riches fairy tale. His life began in very humble circumstances. Born illegitimate, he grew up in the workhouse. After emigrating to America in his teens, he fought on both sides of the Civil War, became a news journalist and started his career as a traveller. His fame exploded with the publication of his book about the expedition to find Livingstone, who had become lost while searching for the source of the Nile.

These days, his reputation is controversial. His treatment of the local people he dealt with was cruel and he was instrumental in helping king Leopold of Belgium establish a colony in the Congo which became notorious for its human rights abuses.

Arguments about colonialism and human rights in Africa, though rightfully prioritised now, were not at the top of the nineteenth century mind. Stanley was a celebrity, in part due to his own self-promotion (he was a professional journalist as well as an explorer) and every aspect of his life was reported with breathless excitement.

The wedding of the century

According to our newspaper report, the expedition ring was returned to him as a marriage gift. Nineteenth century gossip claimed that Stanley had proposed to half a dozen women before being accepted and marrying at the age of 59. He had at least one prior engagement, to the artist Alice Pike, who gave up waiting for his return from a lengthy expedition and married someone else.

His next engagment fared much better. His wedding to the Welsh artist Dorothy (Dolly) Tennant was celebrated at Westminster Abbey on 12 July, 1890 . According to The Illustrated American’s account ‘no wedding, not even a royal one, has created such universal interest in our days as that which took place on July 12 in Edward the Confessor’s Abbey of St Peter’s’

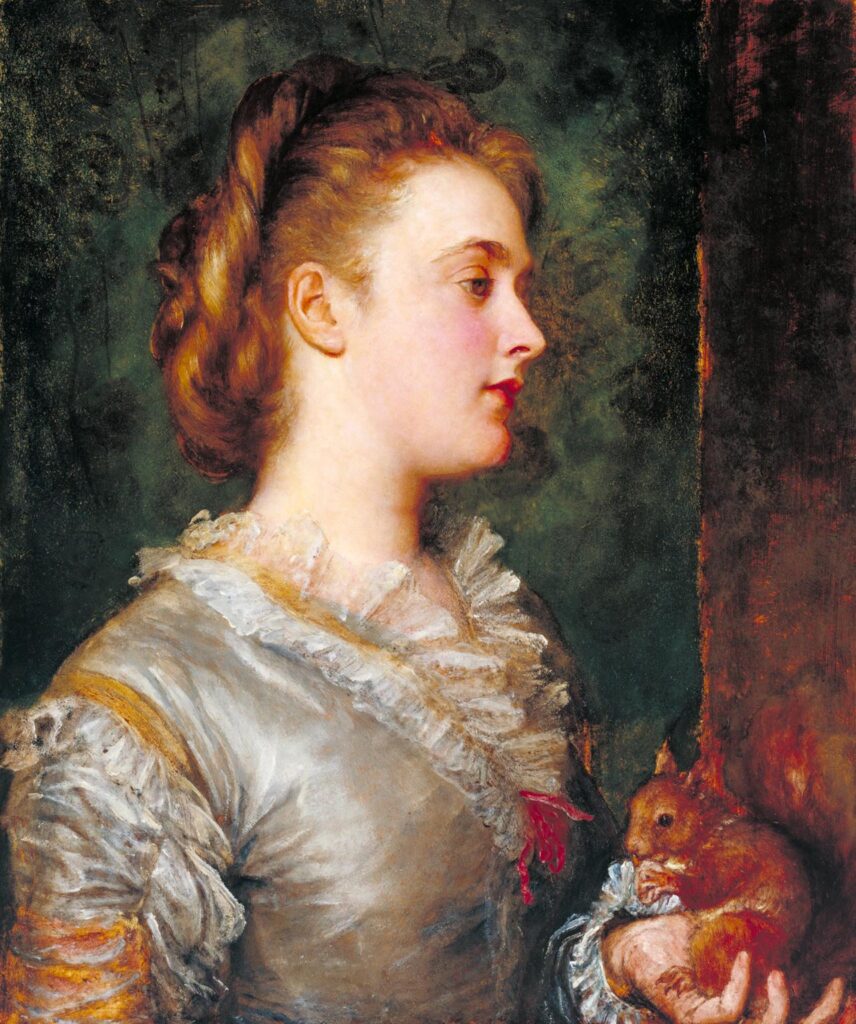

Dorothy Tennant later Lady Stanley, by George Frederick Watts, Tate Gallery

Accounts of the wedding are full of intriguing details. The groom, struck by an attack of gastritis, was so ill that he could barely walk up the nave and it was feared that the ceremony would have to be abandoned.

Stanley’s famous African journeys were much to the fore. Perhaps as a publicity stunt, the bride carried a wreath of flowers with the letter L, which she placed on Dr Livingstone’s tomb, before proceeding up the aisle. The wedding favours were little satin bows hung with a silvered card cut out in the shape of Africa and a line showing the route of the Congo river, which had been mapped by Stanley.

‘Hundreds of wedding gifts’

The Illustrated American recorded that the couple received ‘hundreds of wedding gifts’. Royal gifts included a miniature portrait of Queen Victoria painted on enamels and set with diamonds and pearls which Dolly wore from a necklace, a gold and ivory casket from the King of the Belgians (made from the tusks of Congo elephants?) and a gold inkstand from the Princess of Wales. Dolly Tennant received some magnificent jewellery, including an anchor jewel set with rose-diamonds from the novelist and song writer Hamilton Aidé, a diamond set fan, a tiara and much more. Stanley gave her a sapphire and diamond necklace, a diamond and pearl rose-bud brooch and two moonstone hearts.

Unusual gifts

The gifts ranged from the conventional to the peculiar. Stanley became the proud owner of a silk flag from the American state of Delaware, painted with the words ‘Delaware’s Tribute to H.M. Stanley’ and a bronze plaque from Missouri, similarly inscribed. The Governor of the State of Idaho, George L. Shroup, sent a pair of gigantic elk horns, seven foot long from tip to tip. Prime Minister William Gladstone handed over his seven volume autobiography ‘Gladstone’s Gleamings’. Something to while away a dull winter evening, perhaps. According to our original newspaper account, the little silver ring found its way home as part of this cavalcade of gifts, not the largest or more expensive by any means but with a unique history and pedigree.

Famous names of British and American society contributed – the industralist Henry Carnegie, Shakespearian actor Henry Irving and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts. Stanley’s role in the ill fated Emin Pasha Relief expedition, which attempted to retrieve the Egyptian governor of modern day South Sudan, was rewarded by a diamond tiara from the expedition chairman.

The couple were also presented with one of the only four phonographs or record players to be found in England at the time. A Colonel Gourand had placed the other three in the bell tower, altar and choir of Westminster Abbey to record the singing and bells at the wedding. He gave the new couple a phonograph and the recordings so that they could enjoy revisiting their wedding.

Presentation rings

The notion of a presentation ring was not an original one. Rings were given as court gifts, gem-set rings handed out to ambassadors and courtiers but also presented to mark professional success. Musicians, actors, authors and scientists frequently received rings to mark their successes. When Birmingham worthies presented a diamond ring to author Charles Dickens, he wrote to a friend in delight:

Nothing could be more welcome to me than such a mark of confidence and approval from such a source, nothing more precious or that I could set a higher worth upon’.

Rings also marked military campaigns. In 1883, the Aberdare Times reported the success of local boy Herbert Evans as a soldier at the 1882 battle of Tell-el-Kebir. This was the defeat of the Egyptian army by the British forces, part of the struggle for control of the Suez canal. Herbert Evans was reported as the ‘youngest soldier who had volunteered at that critical moment for such service’. When he returned home, uninjured and in time for Christmas, his local friends gave him a ‘massive gold ring …engraved with the word Tel-el-Keber’ and a purse of money.

Was the silver ring sold by Christies the one which Stanley wore when searching for the source of the Nile? Was it presented to him as a subsequent record or maybe even made as a souvenir for someone who wanted to be associated with him? I’d like to think that it’s the ring which Stanley wore in Africa and which returned to him as one of the oddest wedding gifts on record.

To read more about the history of men’s rings, here is the story of how nineteenth century friends exchanged rings as gifts.

I am the current owner of the ring. It is amazing to think of what it is and where it has been.

How fantastic! What a cool thing to have -it clearly meant a lot to Stanley.