Making jewellery in a time of war: unusual materials

I gave a lecture on jewellery in the two great World Wars recently. One of the questions I was asked was ‘What were the most unusual materials used for making jewellery in a time of war?’

Rumour: jewellery will be frozen!

This was the heading for a Vogue article in February 1943. Was it even possible to make and buy jewellery during a major war?

Wartime conditions were difficult for the jewellery trade. Jewellery was, understandably, not a priority activity. Many of the materials which jewellers used were also vital for the military. Copper (necessary for alloying silver) was also used for shell cases and fuses. Platinum, the key element in the delicate gem-set jewellery of the early twentieth century, was also a vital ingredient in munitions making and other wartime needs. Gold wasn’t directly used in armaments but it was essential to pay for imports of food, weapons and other materials. Even gemstones were harder to find because the routes used to trade them were disrupted by war.

Nevertheless, people still wanted jewellery. Even people in prisoner of war or detention camps made jewellery as souvenirs, for trade or as gifts for loved ones. Soldiers in the first World War trenches used their downtime to make jewellery from recycled materials as gifts and for sale. And, on the home-front, humble jewels made from wool, fabric and buttons cheered people up.

So, if you couldn’t get precious metals or gemstones, what else might you try?

Making jewellery in the trenches

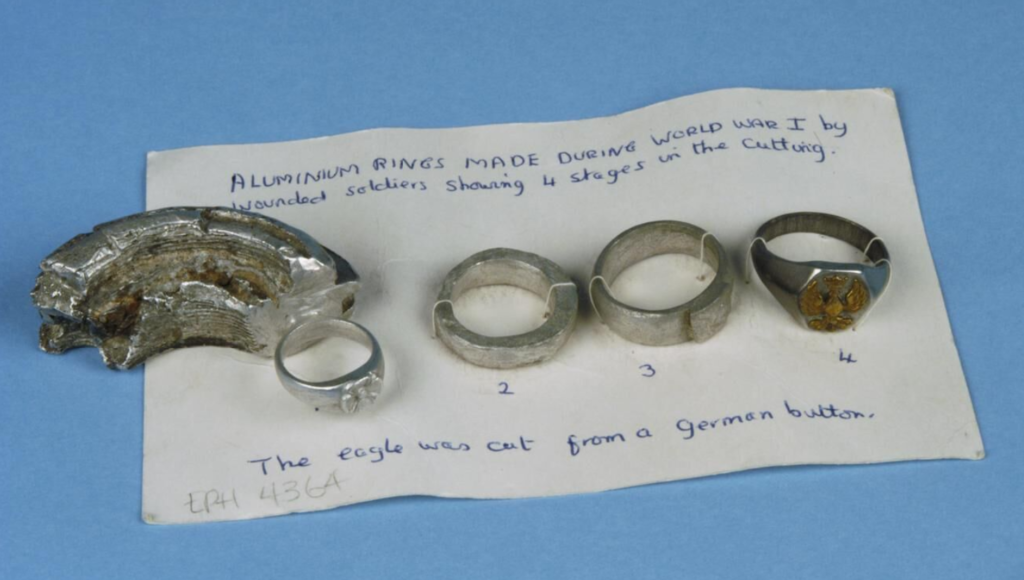

Making jewellery could be a way to survive the worst moments of war. It gave people a moment of peace and creativity, a distraction from the horrors around them. Soldiers in the first world war trenches, or the wounded in hospitals made jewellery to raise their spirits and to sell for small luxuries. They used the detritus of war which lay around. Pieces of shells, weapons, uniforms and scrap metal were pressed into service. Injured soldiers recovering in hospital made the rings below. They show the steps in which a shell fragment and a German uniform button became a ring.

Imperial War Museum

Tasmanian Sapper Stanley Keith Pearl made beautiful pieces of art from the wreckage of the battlefield. He made a stand for hat-pins in the shape of a daisy, with some pins made from uniform buttons. It’s hard to believe that this delicate object is made from the nose of an 18 pounder shell and a shell case, bicycle spokes and a ‘rising sun’ collar badge.

Make do and mend: jewellery from domestic materials

‘Make do and mend’ was the slogan used in Britain during the second World War. It encouraged people to make their own clothes or mend those they already had. Rather than trying to buy new, reusing and repurposing what you already had was key. And making a cheerful accessory from household supplies was easy and cheap.

A homemade accessory ‘… will steal the eye from last season’s outfit’

Vogue, March 1944

Suzanne Petter wrote a series of articles for WWII women’s magazines to teach people how to make their own jewellery and accessories from buttons, wool and scraps of fabric. This wasn’t just fun. It was a way to cheer up a dreary patched or darned outfit. Even if you couldn’t get hold of new clothes (and with rationing, if you didn’t have any clothing points, you couldn’t buy anything), you could feel better about what you did have. Modern Woman ran her pattern for croched bracelets – billed as a way ‘to make a plain wool frock look like a model’.

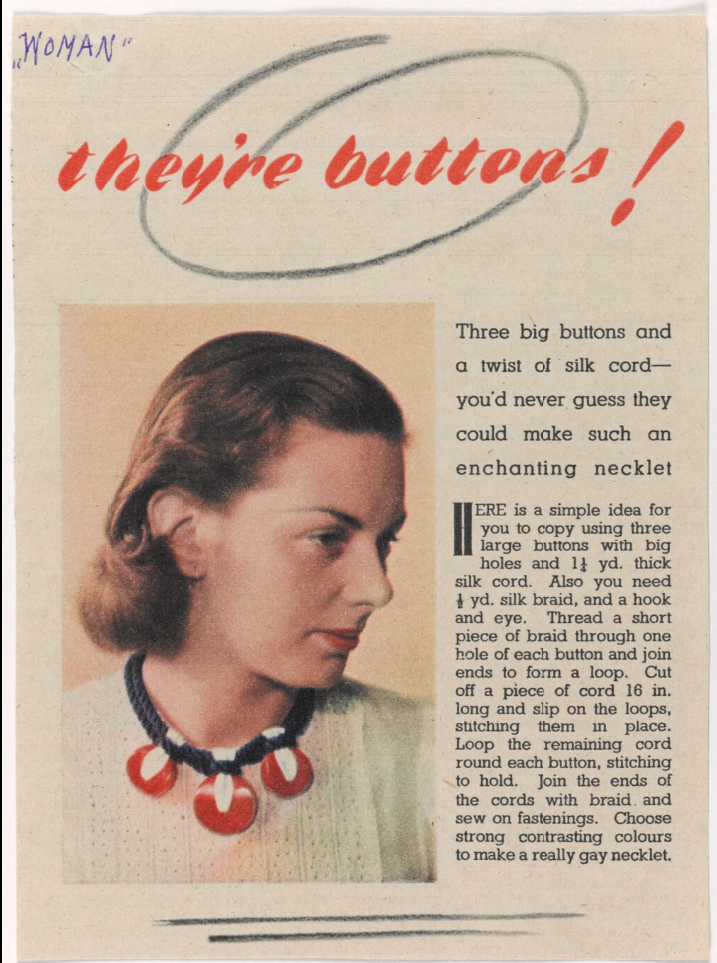

Buttons were the perfect thing to make a striking and colourful necklace. They could be carved, painted and have holes drilled into them. They were big enough to make an impact, cheap and light and, crucially, not rationed.

Three big buttons and a twist of silk cord- you’d never guess they could make such an enchanting necklet.

Suzanne Petter in Woman

Image from Suzanne Petter’s papers in the Imperial War Museum archive.

Birds of freedom and love hearts from a prison camp

1942 – 1945

Poston Relocation Camp, AZ

Made by Yoneguma and Kiyoka Takahashi

Manzanar National Historic Site

In 1944, after the Japanese army attack on the American port of Pearl Harbor, there was a great worry about the loyalties of Japanese American citizens. An order was passed to compel Japanese Americans and their families to report to interment camps. People had very little notice and could only bring the most essential items. Conditions in the camps were difficult but people tried their best to endure them and find what joy they could.

Manzanar National Historic Site

The camp inmates made jewellery from scrap materials around them and natural materials like shells and feathers. Beautiful little carved birds made out of scrap timber and wire from the barrack windows were a symbol of hope and freedom. Flower pins made out of shells replaced real flowers for funerals and weddings. These jewels, made from the humblest materials, show the inmates desire to endure and to make their lives as full as possible.

Making jewellery from the remains of crashed planes

The second World War stretched into the South Pacific. The windows and interiors of downed planes offered plenty of perspex to make into cheap but pretty jewels. Small workshops in places like New Guinea made jewellery from scavenged metal and perspex, often personalised for the buyer. Australian servicemen bought or commissioned them to give to their wives and girlfriends or as souvenirs.

This pretty necklace was inspired by the Southern Cross. Warrant Officer Jack Robert Keen probably bought it for his wife Faith while he was serving in New Guinea.

Although Jack Keen was parted from his wife and children, sending home a piece of jewellery was a way for him to show that he was thinking of them. And, for Faith, wearing the necklace kept a little piece of him close to her.

Perspex and brass wire, 1944-45.

Australia War Memorial

Why bother with jewellery in wartime?

Even though the war years were full of dreadful suffering and loss, jewellery, which seems so superficial, was important to people. Making a jewel from what you had at hand – whether the salvaged wood and metal of a prisoner of war camp, the nose of a shell in the front lines of the First World War or a bit of wool and a button on the home front was a way to show that life and love persisted. A jewel, even if made from the humblest materials, was a sign of defiance and hope.

More on war

Jewellery was also important to a soldier prince in the 19th century Boer War. The story of the ‘A fine young fellow full of pluck and spirit’ shows how a sentimental locket taken to war became a comfort to a grieving mother.

A fascinating insight into the important role jewellery plays in the spirit of endurance during trying times. Jewellery was a prop for me on a daily basis during the pandemic. Worn in isolation, it embodied the conviction that “this too shall pass!”

Eye catching topic for reading and get inspired!

My grandmother told me about the government asking patriotic citizens during WW1 to hand in their gold jewellery for the war effort and a replica in a base metal would be returned to any sender. What was this base metal called?

Hi Ann,

A few countries had similar programmes – though Britain never had to go that far. There were certainly jewellery donations in the UK but no official replacement jewels.

In Germany, the replacement jewellery was generally iron. There was a tradition of giving up gold for iron. The slogan ‘Gold gab ich fur Eisen’ (I gave gold for iron’) often appeared on the replacement jewellery. It’s said to have started in 1813 to fund the wars in Prussia and some very pretty Berlin ironwork jewellery was made as a response. It happened again in both world wars, not just in Germany but also in Italy and Greece.

The Imperial War Museum in London have an iron wedding ring which belonged to Adele Frankl, who gave hers up in WW1. Being Jewish, she fled Germany in WW2 but continued to wear her iron ring https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30084400.

So, depending on where your grandmother was living, it could be iron or possibly a base metal alloy.If you still have it, a jeweller would be able to identify it for you. It’s an interesting bit of family history!

My mother has several pieces of soldier made jewelry from the Australian 2/6 Battalion when they were engaged in the Wewak Campaign. One is a bracelet of what looks like tin with 3 seashells on either side as part of the band. the tin plate has a sun setting over the ocean with Wewak 1945 etched. the other pieces she has are 2 silver rings made from coins, that had the unit colors from a colored toothbrush.

That’s fascinating and so moving. The Australian War Memorial Museum has a great article on ‘Tek Art’, made from the servicemen’s toothbrushees. https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/blog/tek-art I’m not sure if this was uniquely Australian or if other forces had suitably colourful toothbrushes. Thanks for sharing this.