S is for Skull: understanding symbolism in jewellery

In the alphabet of jewellery symbolism, S is for skull. Skull jewellery might feel like the preserve of the modern teenage Goth but it has a long and intriguing history. With gaping eye and nose sockets and a mouth full of teeth, a skull is the most recognisably human part of a skeleton and a jarring reminder of death.

The skull in jewellery is a potent reminder of mortality but, when you set it with gems, it can be gloriously decadent and Gothic. Jewellers have used skulls in religious jewels, as fashion and even for entertainment.

In 1520, Daniel Hopfer made a print which sums up the appeal of skull jewellery. In his drawing, a ragged skeleton holding a skull and a frightening devil follow two finely dressed women who are wearing expensive jewellery. Although the women are enjoying the luxuries of aristocratic life, death and the devil are at their heels, showing the hollowness of secular life. Skull jewellery is a symbolic way to show that even in life, we are always on the edge of death.

Remember that you must die…

By its nature, your skull is only visible after you die. So, looking at a skull, perhaps on your gold signet ring is a powerful reminder of mortality. Memento mori or ‘remember that you must die’ jewellery was enormously popular in Renaissance Europe. Christian theology taught that while life on earth was full of pain and sin, a better future was waiting for the redeemed soul in heaven. Daily life and business were important but not nearly as vital as ensuring that Christians had a good death and the promise of eternal life.

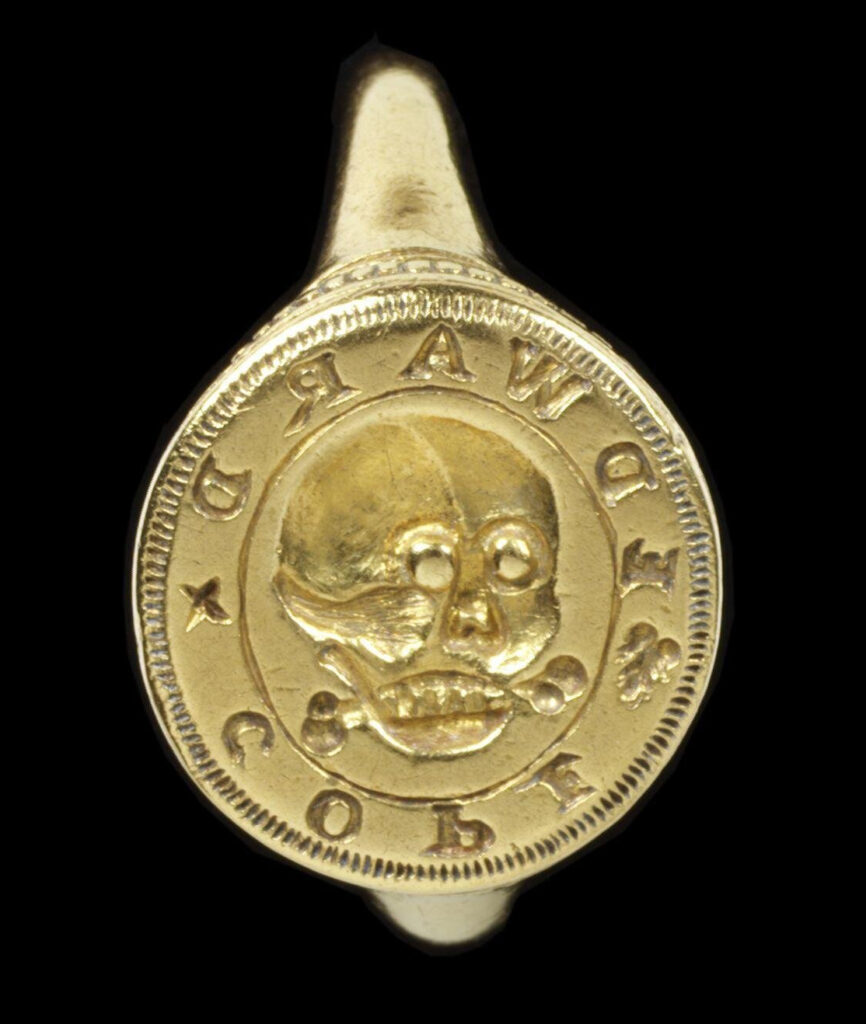

Jewellery decorated with skulls, cross bones, and even entire skeletons was a way to wear a daily reminder of what was truly important and also to advertise your faith. A skull signet ring, like the one made for Edward Cope in the mid 16th century, combined a useful jewel with a reminder of death. Not only did Cope’s ring have a skull clutching a bone in its teeth on the bezel but the back of the ring was set with a piece of actual bone (was this human or animal?). The back of the ring is set open so that the bone, like a religious relic, can touch the skin directly.

Cope wasn’t the only person to choose a skull for his signet ring. Skull rings were set with revolving bezels (skull on one side, personal mark on the other) or with expensive gemstones, like this glorious diamond and enamel ring.

Signet rings, rosary beads, combs, pendants and brooches were all decorated with emblems of mortality in Renaissance and early modern Europe. In an age of wars and plagues, death must have felt ever present.

Know yourself…

Behind the popularity of skull jewellery was the idea of self knowledge. Acknowledging mortality was a way of facing up to the realities of life. This idea comes through strongly in a ring set with a white enamelled skull and engraved with the motto ‘Nosse te ypsum’ (Know yourself). It was made around 1550-1600

In 1617, Nicholas Fenay of Yorkshire left a very similar ring to his son:

‘having these letters NF for my name thereupon ingraved with this notable poesie about the same letters NOSCE TEIPSUM [sic know thyself] to the intent that my said son William Fenay in the often beholding and considering of that worthy poesye may be the better put in mynde of himselfe and of his estate knowing this that to know a man’s selfe is the beginning of wisdom’.

This fabulously grotesque pendant boasts a coffin, with four resident skulls, a hanging skull and a chain of crossbones. The German inscription can be translated as ‘Here I lie and wait for you’.

Jewels set with little coffins were a tiny version of double decker tomb monuments which showed an image of the decaying corpse under the lifelike effigy on the top.

Although the concept is grisly, the jewel is beautifully made. It’s an elegant piece of fashionable jewellery as much as a reminder of death and eternal life. The black enamel symbolises death while the white enamel is a faithful recreation of bones.

The electrical skull

If S is for Skull meant death and the resurrection to the early modern wearer, by the nineteenth century, things had lightened up. Nineteenth century skull jewellery could be much more entertaining. Electrifying skull themed tie-pins were a sensation at parties. The Victoria and Albert Museum hold one of the only surviving electric jewels, a skull pin which still has the electric terminals but which has lost its tiny battery.

At the Paris Exhibition of 1867, Auguste-Germain Cadet Picard showed electrical jewels based on the invention of Gustave Trouvé. Trouvé had combined the new and exciting ability to make tiny electric batteries with jewellery, creating ‘electro-mobile’ jewels. Trouvé’s ‘Lilliputian battery’ could be hidden in a jacket pocket and discreetly switched on and off. A writer from La Nature described the sensational effect at a party in Paris in 1879:

Suppose you are carrying one of these jewels below your chin. Whenever someone takes a look at it, you discreetly slip your hand into the pocket of your waistcoat, tip the tiny battery to horizontal and immediately, the death’s head rolls its glittering eyes and grinds its teeth.

Kevin Desmond, Gustave Trouvé: French Electrical Genius (1839-1902)

It’s fair to say that they didn’t meet universal approval. In 1877, Charles Blanc felt that jewellers were working too hard to find novelties, at the expense of good taste:

Occasionally, the French jewellers allow themselves to be mislead by the fever of emulation or the desire of exciting astonishment. In our exhibitions electric jewels of startling novelty have been displayed. A Voltaic battery, small enough to be carried in the pocket, gave movement to a number of miniature objects arranged for the hair, as brooches or pins; a rabbit played a drum; a silver head, with ruby eyes and enamelled lips, made horrible grimaces; a convulsed butterfly and a bird flapping its wings were also represented, with numerous other toys, no doubt manufactured for exportation, and well calculated to delight savages.

Charles Blanc, Art in Ornament and Dress, 1877

It’s quite a comedown – from a serious examination of mortality to a party piece. If you want to try to make your own electric skull pin, the University of Victoria produced a fascinating kit and set of instructions.

Further reading

For more on jewellery symbolism, try A is for Anchor, B is for Butterfly or M is for Moon.

Memento mori jewellery is well covered in Sarah Nehama’s In Death Lamented: the tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry (2012)

Here is a quick list of books on sentimental jewellery.