A is for Anchor: Understanding symbolism in jewellery

Jewellery is a visual art – it’s made to be looked at and it sometimes carries a message. The language of jewellery is full of symbolism, images which were once widely understood but now often forgotten. Understanding symbolism in jewellery allows us to appreciate its artistry at a deeper level.

A for Anchor

Anchors are made to hold us down, a firm point in a tossing sea. They can be found in love, mourning and religious jewellery. The image of the anchor held a number of entwined meanings, familiar to those who chose and wore this sort of jewellery.

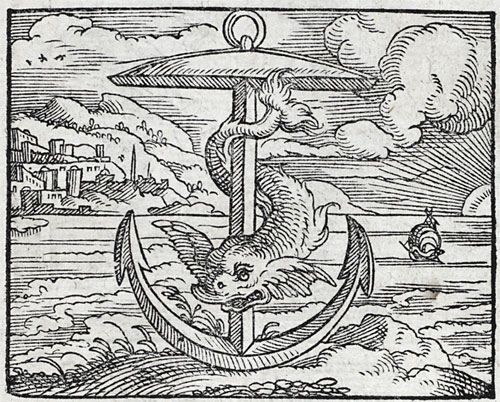

Books of devices or emblems were printed in the Renaissance to explain the visual imagery used in art, jewellery and architecture. Designers and makers took inspiration from books of emblems to make jewels which were both beautiful and symbolic.

Andrea Alciato (1492-1550)’s Emblemata was one of the best known sources of designs. In this image, he used an anchor to represent the qualities of a ruler. Just as an anchor held a ship firm in a stormy sea, princes kept their subjects safe. Therefore, an anchor in Renaissance jewellery could represent political stability.

Andrea Alciati, Emblema VIII: Princeps subditorum incolumitatem procurans

In 1602 when visiting Harefield House, Elizabeth I received a gem-set jewel in the shape of an anchor to signify that ‘wherever you shall arrive, you may anchor safely, as you do…. in the harts of my Owners.‘ The symbolic jewellery given to Elizabeth represented her importance as the embodiment of the nation.

Elizabeth wasn’t the only Renaissance ruler to own a gem-set anchor jewel. The Scottish jeweller James Heriot made at least four anchor jewels for Anne of Denmark

The anchor as symbol of hope

The anchor is also an ancient Christian symbol representing hope. The Epistles to the Hebrews describe faith in God as ‘This hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast’ (Hebrews 6:16-19).

The anchor is often shown with a cross for faith and a heart for charity as symbols of the three cardinal virtues, like this necklace design from the 19th century jewellery firm of John Brogden. The shape of the anchor echoes that of the cross and is often shown with a rope twined around it.

Jewellery design from the John Brogden album, ca. 1860. Victoria and Albert Museum

As well as the anchor itself, it is often accompanied by a female figure used as the personification of Hope.

Later eighteenth century mourning jewellery uses images taken from classical art. Funerary urns are set on columns or altars and women wearing draped robes mourn by monuments.

The melancholy woman on the bezel of a ring, made to mark the death of John Chalmers aged 57, is holding an anchor – a representation of the hope of resurrection into eternal life.

Gold mourning ring, 1786. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The naval anchor

Sometimes an anchor really is an anchor. Jewels made for naval men often included anchors in their design. A drawing by Thomas Cletscher, ca. 1642, for a pendant showed an anchor set with diamonds with seven large pendant pearls. It was intended for the Duke of Buckingham when he was Lord High Admiral although, sadly it does not survive.

The great British naval hero Horatio Nelson died in 1805 from his injuries at the Battle of Trafalgar, fighting against the French forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. Nelson’s death was marked by great public mourning. He was granted a state funeral with a procession through the centre of London and burial in St Paul’s Cathedral. When Nelson died, he asked for his hair to be cut and sent to his lover Emma Hamilton.

Nelson’s hair appears in a number of mourning jewels, like this pendant set with his portrait and locks of his hair arranged in two wreathes. The glass cameo portrait is surrounded by pearls, symbolising tears. An anchor, also set with pearls, hangs from the portrait. The anchor symbolised hope and Christian faith, as was the custom in 18th mourning jewels, but it must have surely also referred to his naval prowess.

Mourning jewel for Nelson, ca. 1806. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Anchors in fashion: wedding jewellery

Navally inspired fashions were extremely popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sailing was a hobby for the wealthy, carried out in regattas and yacht clubs. Children wore sailor suits and ribbons decorated with the names of ships. In 1896, Vogue magazine praised

‘diamond anchors and chains, beautifully designed and very, very fit for the yachting gown ornament.’

Vogue, August 20, 1896

Anchors also found their way into naval themed weddings. When Lillian Smith, the daughter of a sea captain married Captain McLean of the steamship Woodonga in 1904, she chose a very suitable nautical theme. According to the newspaper reports, the marriage took place on the quarter deck of the ship. Lillian wore a pearl and diamond necklace with an anchor locket. Her bridesmaids were in sailor dresses and carried anchors of flowers to match the gold anchor brooches Captain McLean gave them.

Lillian Smith and Captain McLean weren’t the only couple to choose naval imagery for their wedding jewellery. The great society marriage of the late 19th century was that of the Duke of York, the future George V to Princess Mary (known as May) of Teck. It took place in 1893 with great fanfare.

The bridesmaids received a bracelet with a very symbolic jewel at its centre. It was decorated with an enamelled white rose for Yorkshire and a diamond anchor to symbolise the Duke’s naval career. Society weddings always attracted public interest and copies of the brooch were advertised for a ‘very trifling sum’ at the Burlington Arcade. The jewel could be worn as the centrepiece of a bracelet and also as a brooch.

‘Rose of York’ brooch, Collingwood and Co, 1893. Royal Collections Trust.

Understanding symbolism in jewellery: the anchor

Anchors have been used in jewellery since the Renaissance. They can symbolise political stability, Christian faith and hope of the resurrection, love expressed both in life and death and they made appropriate jewels for naval men and their brides.

By understanding symbolism in jewellery, we can place ourselves in the minds of the makers and wearers of these intriguing jewels.

Further reading

To learn more about symbolism in jewellery, try B is for Butterfly, M is for Moon and S is for Skull.

A brief history of wedding jewellery for bridesmaids.