White heather and Fumsup – lucky jewellery in the First World War.

It’s hard to imagine the feelings of a soldier heading to the battlefields of the First World War. The optimism of 1914 and the belief that the war would end in glorious victory by Christmas soon faded. By 1915, news of the slaughter on the Western Front was well known and many families had received the dreaded telegram. One way to manage anxious uncertainty was by giving soldiers lucky jewellery to take to battle with them. Families bought the heavily marketed ‘Fumsup’ dolls, alongside shamrocks, white heather, horseshoes and many homemade good luck tokens.

These tokens brought comfort if nothing else. When Trooper Harold Greenhill of Leicester wrote to his wife in May 1915, he told her:

‘We have been in the trenches and know it. Nearly all our officers gone, and a tremendous lot of our men. You will probably see the casualty list. I am quite all right. I wore your charm around my neck the morning before we went in and it seemed to bring me good luck. We were in a perfect hell’.

The Leicester Daily Post, Friday 21 May, 1915

Post a ‘Fumsup’ for luck

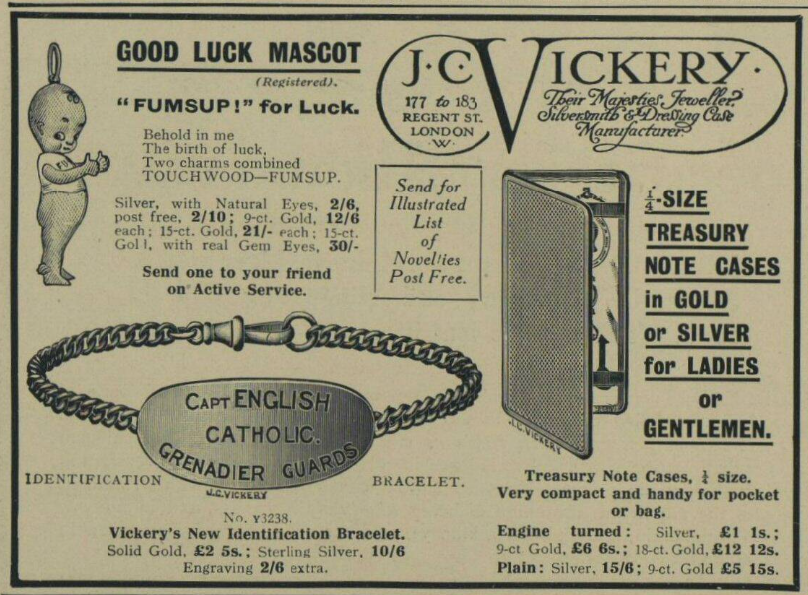

The wood and metal ‘Fumsup’ doll had been popular since the late nineteenth century but gained a special relevance during the war years. An advert in the Daily Mirror, 13 December 1915 makes the point clearly:

‘Sure you’ve many friends away. With whom you’d wish Good Luck to stay. That’s so! Then write your jeweller to say. ‘Post a Fumsup Charm to-day’.

It was ‘The Xmas Present for Fighting Men at Home & Abroad’.

This rather horrible little doll combined several good luck traditions – thumbs up hands and a wooden head to be touched for luck. It had little Cupid winged feet to bring the soldier back safely to his loved ones. Some versions also had a four leaf clover set into the body. It was small enough to fit in a pocket, or on a chain around the neck and they were produced in huge numbers. .

Image: Imperial War Museum, London

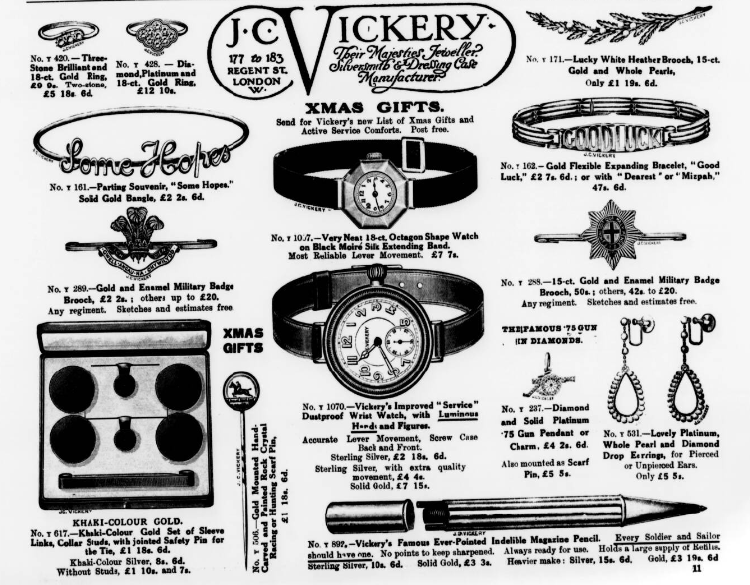

J.C.Vickery seem to have specialised in jewellery for soldiers and their loved ones. Their advert in the Illustrated London News, May 13, 1916 juxtaposes the lucky ‘Fumsup’ with a grimly practical identification bracelet, bearing the name, rank, unit and religious affiliation of the wearer.

‘Many, many thanks for the white heather’

White heather was naturally rare and has long been a good luck token, never more so than during the war years. An advert in the Lancashire Echo, 28 October 1914, listed heather, alongside elephants in gold and silver and African beans, as lucky talismans which were much in demand.

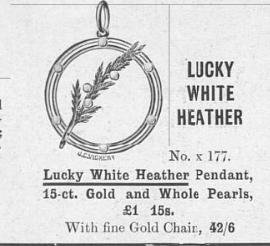

Families posted sprigs of white heather to their boys at the front but jewellers also offered more lasting options. J.C. Vickery’s white gold and pearl ‘Lucky White Heather ‘ pendant was on sale for a modest 35s or a slightly fancier version for £1 15s. Although it’s quite a delicate jewel, it was clearly intended to be worn by soldiers as well as their female relatives.

When a thousand men from the Hallamshire Regiment left Sheffield on 4 November 1914, they paraded through streets hung with flags. After being addressed by the Lord Mayor, each was presented with a sprig of white heather tied with patriotic red, white and blue ribbons, presumably to be worn as a lucky charm. Poignantly, most of the remaining newspaper page is filled with columns of the dead, wounded and missing.

Some soldiers pinned heather to their caps . When Private James Anderson wrote to his sister in October 1915, he described wearing the white heather she had sent him while his troop was inspected by Sir Ian Hamilton. Hamilton congratulated him on having ‘a piece of the right stuff.’ The Dumfries and Galloway Advertiser of October 6 1915, reported that an English soldier had been sent a sprig of white Scottish heather, pinned it to his hat and that ‘though his company was engaged in the bloodiest of the fighting and suffered dreadful losses, yet he escaped without a scratch. After that, who will say that white heather from Dumfries is not lucky?’

An article entitled ‘Plain talk to slackers‘ (Forres, Elgin and Nairn Gazette, 1 September 1915) made the dangers of war clear: ‘We were on fatigue last night from 6pm until 2am, digging, digging, digging. I never saw any party dig like we did. Bullets were as plentiful as the flowers in May, and therefore the deeper we made the trench , the safer we were. We were very lucky, only one being hit and not seriously.’ The author goes on to give ‘Many, many thanks for the white heather. I kept a bit and distributed the rest. What a rush there was for it!’

Civilians also wore sprigs of white heather in their buttonholes and hats, perhaps hoping for luck for their loved ones. White heather sales supported war fundraising and charities like the National Relief Fund for wounded soldiers and their families. Many war brides carried white heather in their bouquets, sometimes tied with ribbons in the regimental colours.

The lucky four leaf clover

Shamrocks and four leaf clovers are still considered good luck charms.

This little locket holds a four leaf clover and ladybird, probably a homemade charm. It was collected by the anthropologist Edward Lovett who made a study of World War 1 soldiers’ tokens.

According to the contemporary press, the German Kaiser carried a four leaf clover in his pocketbook and jewellers used this as a way to market their own clover jewellery.

Image: Imperial War Museum

Four leaf clovers were in such high demand that the Irish government sent supplies of them to their troops to wear on St Patrick’s Day.

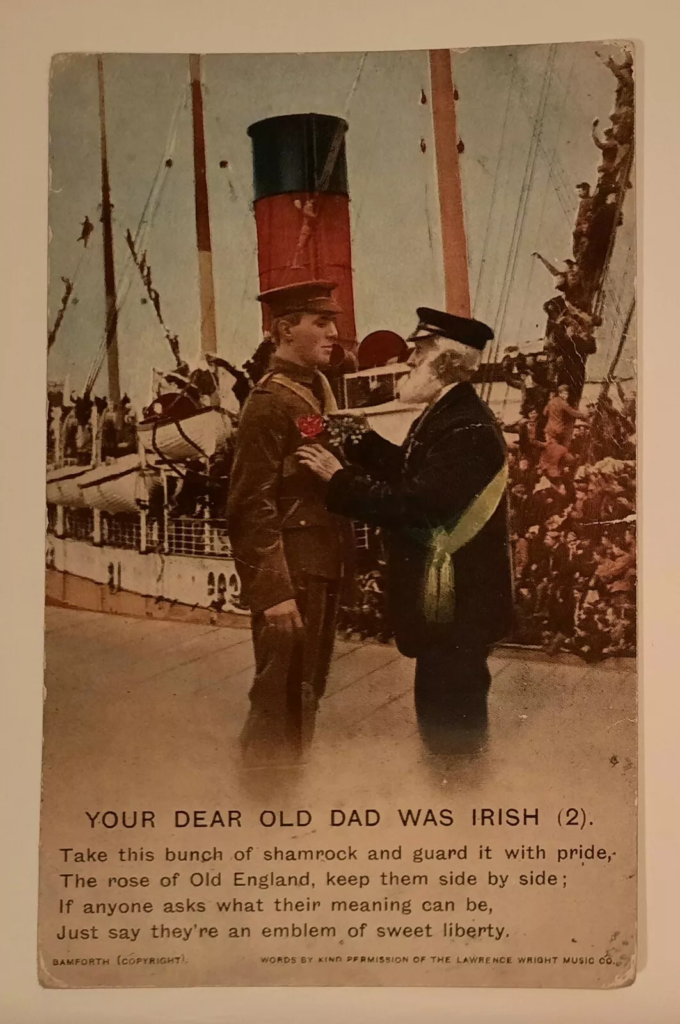

Bamforth made hundreds of patriotic postcards during the First World War. In this example, a young man is leaving for war with a bunch of shamrock pinned to his jacket , alongside the ‘rose of Old England‘ . If asked, they are to be explained as ‘an emblem of sweet liberty‘.

Swastika jewellery will bring you good luck

It may seem surprising in view of the corruption of the swastika symbol in the Second World War, but swastika themed jewellery was a popular good luck token for soldiers. The swastika was an ancient symbol of well being in India, China, Africa, native America and Europe.

Swastikas were placed on jewellery, textiles and domestic goods. The British government even sent specially branded ‘Swastika’ cigarettes to soldiers, according to the report in the Police Gazette, 27 October 1916, that thieves broke into a warehouse and stole thousands of the lucky cigarettes. Tobacco was one of the most keenly sought after items at the Front and many charitable organisations were set up to provide ‘Smokes for Tommy’.

‘Bow! Wow! the Empire Mascot

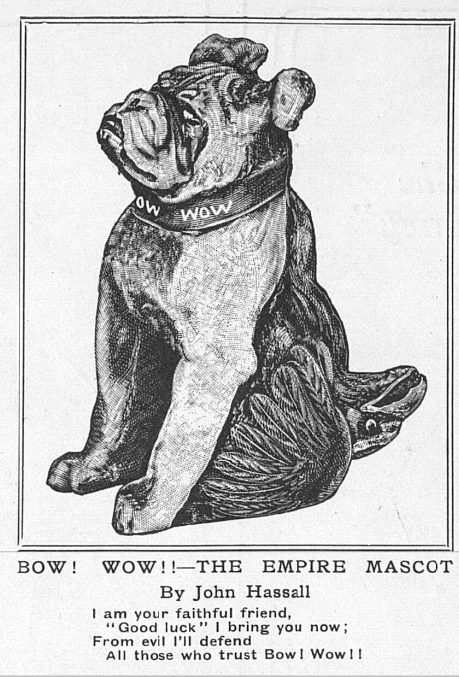

In 1915, the poster artist John Hassall designed a ‘wonderful “Luck” bringer, showing how the Bulldog turns down the Eagle.‘ It was a silver and gold charm shaped like a British bulldog, obtainable from all the leading jewellers or from Messrs Badcoe and Hanks, Holborn and department stores.

The figure shows the dog sitting upon the German Eagle, with the motto promising that ‘From now on I’ll defend/ All those who trust Bow! Wow!’

‘Admirals, Statesmen, Society Leaders, Red Cross Nurses, officers and men of His Majesty’s Army and Navy, and their mothers, sisters, sweethearts, and all their relatives are now wearing this emblem of British pluck, endurance and Bull-dog tenacity.’ according to the Daily Mirror of October 11, 1915. So far, I haven’t come across any surviving examples.

‘Some Hopes’

Soldiers wanted lucky tokens to give them some small feeling of comfort or the illusion of safety when going into such dangerous and frightening situations. For their families, sending a lucky token may have felt like a way to help their husband, brother, son or lover.

Crooked sixpence coins, pieces of coal, bloodstones, and other magical objects were all used and soldiers often believed that they escaped from danger because of these lucky amulets.

Almost any object could be made into a lucky mascot. Even pieces of shrapnel removed from soldiers’ wounds were mounted in gold and turned into pieces of jewellery, according to the Daily Mirror, 22 July 1915. Shrapnel caused some of the most terrible war injuries and perhaps it’s unsurprising that those who survived would have transformed it into amuletic jewellery.

Jewellers sold all sorts of lucky objects, suggesting that there was a keen market for their goods. An advert by J.C. Vickery offered lucky white heather alongside an expanding bracelet which read ‘Good luck’ and another with the puzzling motto ‘Some Hopes’.

Lucky jewellery in the First World War could be made by commercial jewellers or be the most humble and home made of objects, but it served an important purpose. Amulets and lucky jewellery were a form of magical thinking, a way to feel safer at points of unimaginable peril. When survival was more a matter of luck than anything else, a mascot or lucky charm was something to hold onto and a way to hope.

Further reading

‘Loss and love in the first world war’ – the story of two young artists and their experiences of the war.

‘A fine young fellow, full of pluck’ a look at the French Prince Imperial and the jewellery which he took into battle in the Boer war.

‘Making jewellery in a time of war: unusual materials’ looks at how jewellers coped with wartime shortages

Owen Davies’ A Supernatural War: Magic, Divination, and Faith During the First World War is an extensive exploration of the role superstition played in the lives of First World War soldiers, including lucky jewellery.

Thank you for the fascinating read!

I came upon this because I have one of the little dog and eagle mascots and was doing some research, the information you have provided is fantastic.

Thank you again

I’m really pleased you found it useful! What a cool thing to own.