Rings as gifts between male friends

Jewellery serves many different functions both practical and emotional. Gifts of rings between male friends were an intriguing part of nineteenth century social life. When we think about exchanging rings, we probably think of romantic love – a link between two people, which is often sexual in nature. However, the emotions of friendship can be just as intense. In the nineteenth century, male friends wrote to each other in highly emotional ways. They also gave each other tokens of friendship such as jewels, objects which were rich in meaning and important to them.

Rings worked wonderfully for this. Men wore them frequently, they were available at different price points and they could be personalised through designs and inscriptions. Most jewels survive without any provenance – we don’t know who bought them or wore them or what they meant to them in life. Despite this, a small group of rings survive which can shine a light on some important male relationships.

A ring for Bouncer, from Kitten and Hosky

Relationships with men shaped the life of writer and dramatist Oscar Wilde (1854- 1900). His disastrous romance with Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (known as Bosie) led to the libel court, and eventually to prison. However, long before Oscar met Bosie, he was drawn to another man.

by Napoleon Sarony

albumen panel card, 1882

NPG P25 National Gallery London (Creative Commons Licence)

As a student at Magdalen College, Oxford in the mid-1870s, his social circle included two friends – Reginald Harding and William ‘Bouncer’ Ward. The three young men called each other by special nicknames – Wilde was ‘Hosky’ and Harding ‘Kitten’. They shared an interest in poetry and the theatre and enjoyed riotous evenings in Wilde’s college rooms. It’s not clear whether Wilde had romantic feelings towards Bouncer but he was clearly sad when he left Oxford.

Wilde and Harding (Hosky and Kitten), decided to buy a parting gift for their friend. They chose quite a conventional 19th-century ring, shaped like a buckled belt. It was the sort of thing which could be found in any high-street jewellers or in the pages of a trade catalogue. In fact, Mappin and Webb advertised a very similar one in their section of ’18 carat gold gentlemen’s rings’. It cost £3 10s.

The inscription inside the ring, however, makes it clear that this was a special gift. ‘A gift of love to one who wishes love’ was inscribed in Greek letters inside the hoop. They also added their initials: “OFOFWW & RRH to WWW 1876” (Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde & Reginald Richard Harding to William Welsford Ward 1876).

The ring was kept in Magdalen College until it was stolen, lost for many years and then dramatically recovered due to the Hatton Garden jewellery robbery. Full account here

‘I wish I had something to remember you by’ : A ring for two Pre-Raphaelite Brothers.

Painters William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais were close friends as well as artistically linked. They founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – a group of artists who were entwined personally and professionally. The Brotherhood wanted to move away from classical conventions and rediscover the artistic style of the middle-ages. They were also interested in early Christian history and Holman Hunt, in particular, made a series of religious paintings.

by Sir John Everett Millais, 1st Bt

Pencil with some wash on paper, 1853

NPG 5834 National Gallery London (Creative Commons Licence) https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw07509/William-Holman-Hunt

Although both men later married, they had a very intense relationship. When Holman Hunt left for Syria in 1854 to further his religious painting, Millais feared he might not survive the journey. The two men created pencil drawings of each other as souvenirs. Holman Hunt thought that Millais’ effort was a good likeness, rejoicing that, unlike other portraits it didn’t make him look like a ‘murderer or a beer-drinking pickpocket’. Millais himself claimed that he was ‘so pleased with it that, as I have no other, I must keep it for myself, but will copy it for you and send it in the course of a week or two.’

Millais found the thought of Hunt leaving very distressing. He wrote to him before he left:

“In truth I don’t think I should have the strength to say goodbye – scarcely a night passes but what I cry like an infant over the thought that I may not see you again – I wish I had something to remember you by, and I desire that you should go to Hunt and Roskell and get yourself a signet ring which you must always wear… get a good one and have your initials engraved thereon…”

Holman Hunt duly went to the London jewellers and bought a gold ring set with a red and white layered sardonyx. Hunt and Roskell were one of the premier Bond Street jewellers. Queen Victoria gave them her Royal Warrant and they exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition.

Holman Hunt asked the jewellers to engrave his new ring with his initials WHH and wore it until his death.

Millais wasn’t the first person to think of a signet ring as a gift of friendship. Louis Mayeul Chaudon’s example letter of 1787 reads:

‘Here it is, my dear FRIEND, this seal that you wanted so much. May it seal for a long time the secrets of friendship! I have had it made with a monogram where our two names are intertwined, just as our hearts are joined. I did not think it possible to engrave it with the emblems you proposed: true attachment must be accompanied by simple ornaments. Our names should suffice &c. &c.’

Signet rings were useful, personal and worn daily – the perfect way to remember a friend.

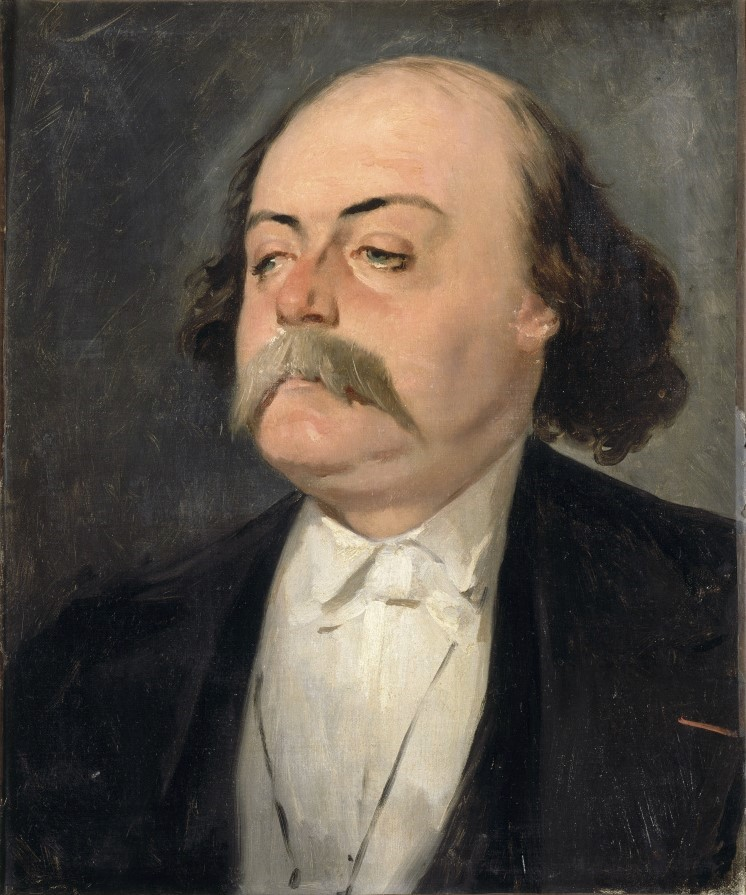

‘A kind of intellectual marriage never threatened by divorce’ : Gustave Flaubert and Maxime du Camp

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Millais and Holman Hunt weren’t alone. The French novelist Gustave Flaubert, author of Madame Bovary, exchanged rings with his friend, the writer and photographer Maxime du Camp.

Du Camp wrote in his memoirs that he gave Flaubert his Renaissance style ring set with a cameo of a satyr. Flaubert in turn gave him a signet ring with his initials and motto. Du Camp made the significance of these gifts clear, writing:

‘When we exchanged rings, it was a kind of intellectual marriage which was never threatened by divorce.’

We don’t know if their relationship had any romantic elements but it was clearly important to both men and deserved a material token to record it.

A ring for Bishop William Ward

William Thomson (1819-1890) was a specialist in logic and theology. He was a fellow of Queen’s College, Oxford, a preacher at Lincoln’s Inn and Queen Victoria’s chaplain. He met the beautiful Zoe Skene (1835 -1913), the daughter of the British Consul in Aleppo and they decided to marry in 1855. Oxford colleges didn’t permit married fellows, so Ward had to look for a new job. After six years as Provost of Queen’s College, he moved into the Church. He became the Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol in 1861, and the next year, moved to York to become the Archbishop.

by Alexander Bassano

half-plate glass negative, 1883

NPG x96180 National Gallery London (Creative Commons Licence)

When Ward left Oxford, his college friends wanted to give him a leaving present. They chose a signet ring, a gold ring engraved with a bishop’s mitre and crozier as well as his coat of arms. He wore the ring all his life and it can be seen on the little finger of his left hand in his photograph above.

To sum up…

Nineteenth century men took their friendships very seriously. They wrote to each other in strong, almost romantic language and weren’t afraid of putting their friendships at the centre of their emotional lives. Giving and receiving rings was a way to mark these important relationships – whether as leaving gifts or the sign of an ‘intellectual marriage’. I wonder how many more rings in museum collections have an emotional back story?

For another post on nineteenth century male jewellery, try the story of the curious locket worn by politician Denis Bowes Daly here.

Every Article surprises me more. Lots of Fresh Ideas!