‘A fine young fellow full of pluck and spirit’

The Prince Imperial’s unlucky locket

A jewel is often a gift of love – sometimes romantic, but sometimes given by a mother to her much loved son. An unlucky locket, given to Louis Napoleon, the Prince Imperial by his mother Empress Eugenie. played an unexpected part in his death in South Africa in 1879.

Exile in Chislehurst

Napoleon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph Bonaparte (14 March 1856 – 1 June 1879) was the only child of the Empress Eugenie and the exiled French Emperor, Napoleon III.

He had an early taste of military life in the Franco-Prussian wars. According to a sketch in the Cardiff Times & South West Daily News, Saturday June 21, 1879, ‘young Louis received his “baptism of fire” at the capture of Saarbruck.’ As his father wrote to his wife, Eugenie,

‘We were in the front rank, but the bullets and cannon balls fell at our feet. Louis has kept a bullet which fell quite close to him. Some of the soldiers wept at seeing him so calm.’

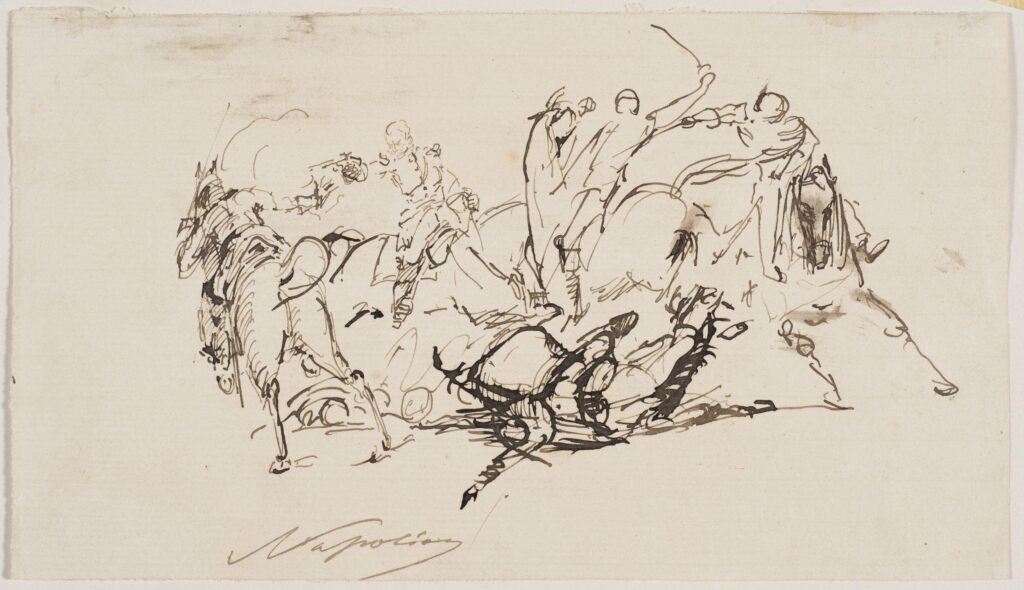

He was fourteen at the time. His reckless bravery was already in evidence. Although his father was proud of him, Republican newspapers were less impressed. A satirical print of ‘Titi Louis’ (little Louis) shows him at the battle of Saarbruck, riding a rocking horse and holding a deflating balloon marked ‘Empire. He holds the famous bullet in his hand.

This moment of victory was followed by a disastrous defeat by the Prussian army, at the Battle of Sedan on September 2, 1870. The royal family left France in exile. Eugenie and her son fled to Camden Place, Chislehurst – now an upmarket golf club and wedding venue in Kent. They were joined by the Emperor, but ill and dispossessed, he died only two years later in January 1873.

Eugenie and her now seventeen year old son were left alone and became extremely close. Not only was he only her only family, but he was the sole hope of those who wanted to bring the Bonaparte family back to power.

‘A fine young fellow full of spirit and pluck’

The young prince studied at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich as a gentleman cadet, completing the military education he had begun in France. He was in a delicate political position, still supported by French Bonapartists but not recognised by the French Republican government with which the British wanted to retain cordial relations. It was therefore impossible for him to take up a British army commission. Nevertheless, he was eager to join the war in South Africa.

The Anglo-Zulu wars were fought between the British Empire and the independent Zulu kingdom of King Cetshwayo as part of the British effort to annex the whole of southern Africa. To the young Prince Imperial, it was a thrilling adventure he desperately wanted to share.

A letter of commendation written by Lord Chelmsford, the Duke of Cambridge, described him as a ‘fine young fellow full of spirit and pluck’ who wanted to see as much as he could of the campaigns in ‘Zululand’. Rather prophetically, he also claimed that his only anxiety on his behalf was that he was ‘too plucky and go ahead.’

The campaign against the Zulus

Victoria and Albert Museum

The volunteer prince arrived in South Africa in 1879 and must have proved a challenge to his hosts, who were required to keep him safely guarded at all times. He was eager to see and join in attacks on the Zulu forces and indeed, joined an expedition in which the British troops burned kraals and attacked Zulu warriors.

His ‘plucky and go ahead’ spirit became his undoing. He joined a mission near Itelezi, where the British troops erroneously thought there would be no Zulu resistance. Louis Napoleon charged ahead. Soon separated from his comrades, he fell from his horse. He died on 1 June 1879, aged only 23, stabbed with at least seventeen assegai thrusts.

A little gold chain with a locket from his mother

His naked body was later found on the battlefield, retaining only a chain around its neck. According to Archibald Forbes in The Century:

‘When the Prince’s body was found next day, all that was left on it was a little gold chain, on which was strung a locket set with a miniature of his mother and a reliquary containing a fragment of the true Cross, which was given by Pope Leo III to Charlemagne when he crowned that great Emperor of the West and which dynasty after dynasty of French monarchs had since worn as a talisman.’

The sword Louis Napoleon carried in South Africa was the same one that the first Napoleon carried from Arcola to Waterloo. Other newspaper reports also suggest that he wore hair medallions – perhaps jewels holding the hair of his parents?

The Prince Imperial therefore went to war comforted by the photograph of his mother, alongside the relics of the French emperors. Sadly, neither was able to protect him. Nevertheless, the report in the Illustrated London News of June 28 1879 claimed that the Zulu warriors had taken his jewellery for powerful talismans and had left them on his body.

A telegram was sent to Britain to advise the government of his death. Lord Sydney was sent to Chislehurst to break the news to Eugenie (the staff had hidden the daily newspapers from her). Eventually, the Prince’s body was embalmed and returned to be buried near his father in St Mary’s church, Chislehurst. Probably the locket returned with the body.

A locket for luck

Both men and women wore lockets and it’s not surprising that the Prince owned one. Photography developed fast, from the development of the daguerreotype in 1839. By the 1850s, the wet plate technique allowed multiple prints to be taken from a single negative. Small photographs were made to fit into lockets and bracelet clasps – a faster and cheaper alternative to painted portrait miniatures. Suddenly, anyone, even on a modest budget, could have a picture of their sweetheart or parent.

Jewellery catalogues advertised lockets with one or two windows to fit a photograph. These lockets were made of gold, silver or plated metal and set with gemstones for the most decorative. Commercial jewellers, like the Birmingham manufacturers, developed machinery which allowed jewels to be made of mass produced segments, bringing the price down even further. The John Brogden album at the Victoria and Albert Museum records hundreds of designs – like the drawing below of pendants or lockets. Perhaps the Prince’s locket looked something like this?

Victoria and Albert Museum

Lockets for young men

Men wore lockets on chains from their necks, like the Prince, or else attached to their watch-chains and tucked into a waistcoat pocket. The Prince Imperial’s locket, bearing a photograph of his mother Eugenie, perhaps combined a son’s devotion with a hope from Eugenie that it would protect him.

Wearing a locket with your mother’s hair or portrait was a way for young men to remember proper conduct. In Louisa May Alcott’s story Silver Pitchers and Independence, Polly gives a locket to her wild young brother Ned:

‘…she transferred a plain locket from her watch-guard to the one lying on the table. Ned knew that a beloved face and a lock of grey hair were inside, and when his sister added, with a look full of sweet significance “For her sake, dear”, he answered manfully, “I’ll try, Polly”.’

When Ned looks at the locket, he is reminded of his deceased mother and her hopes for him. Was Louis Napoleon comforted by the image of his mother on his African adventure?

When Eugenie looked at the locket she had given her son, she must have been reminded of her brave hopes and tragic loss.

A detailed account of the Prince Imperial’s life at Chislehurst https://www.chislehurst-society.org.uk/PDFs/PrinceImperialILN.pdf